Overtourism and Safety of World Heritage Sites

The management of World Heritage Sites (WHS) and significant urban and cultural areas is an increasingly complex challenge. The integration of such sites into the context of globalization brings both benefits and threats. One of the most discussed challenges is the often controversial relationship between Cultural WHS and tourism. Although tourism is considered a vital source of income for the local economy and can attract funding for conservation and restoration, its uncontrolled growth, known as “overtourism”, can have significant negative consequences.

Overtourism does not simply impact the visitor experience or deteriorate the site; it profoundly affects the lives of residents, increasing the cost of living, contributing to problems of crime, overcrowding, waste management, noise pollution and loss of control over heritage resources. This phenomenon generates ambivalent perceptions among heritage managers.

A crucial aspect that seems not to have been adequately addressed in high-density tourist areas and GLAM sites (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums) is the safety of people during emergencies.

Several studies (the 2024 Martin Thomas Falka and Eva Hagsten paper and the 2020 one of Egoreychenko Alexandra Borisovna et Al.) highlight how cultural heritage managers perceive various factors, including tourism and infrastructure, as elements that can have both beneficial and harmful effects. Contrasting perceptions are more frequent in relation to tourism, visitors, recreational activities and land transport infrastructure. However, sites are also threatened by natural risks and intentional acts.

Natural Risks Amplified by Overtourism

Different natural risks pose significant threats to World Cultural Heritage Properties. These include:

- Extreme weather events: storms, droughts, heat waves (implicit in climate change).

- Geological/hydrogeological disasters: earthquakes, floods, avalanches/landslides, tsunamis/tsunamis.

- Fires: forest fires.

- Other environmental factors: air pollution, water pollution, parasites and invasive species.

The studies cited focus mainly on the damage that these natural events can cause to the sites themselves. However, it is essential to consider the impact on the safety of people in overtourism contexts. Overcrowding, a direct consequence of overtourism, makes emergency management extremely more difficult.

In the event of an earthquake, fire or flood, the presence of an excessive concentration of tourists in confined spaces (such as museums, galleries or densely populated historic centers) or in nearby risk areas can hinder evacuation and rescue operations. Transport infrastructures, already congested by daily tourism, become critical points in the event of the need for rapid mass movement. Managers’ perceptions that transport infrastructure is both beneficial and harmful reflect this tension: essential for access, but problematic in terms of impacts (traffic, pollution, wear and tear) and, by logical extension, ineffective or dangerous in mass emergencies. (Note: this direct connection between overtourism, natural emergencies and specific safety during emergencies for people is not explicitly detailed in the papers, which focus more on damage to the site or general perceptions of tourism impacts.)

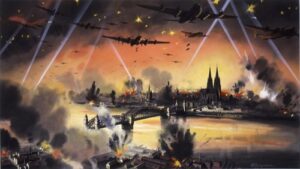

Risks related to intentional acts and overtourism

The sources cited also mention man-made threats, including illegal acts and the deliberate destruction of cultural heritage. Terrorism is a growing and far-reaching threat. World Heritage sites have been deliberately targeted in conflicts and by terrorist groups, as demonstrated by the cases in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria.

In overtourism contexts, where large crowds gather in iconic and often symbolic places, the risk associated with intentional acts takes on an even more critical dimension. The concentration of a large number of people in a single place increases vulnerability and potential consequences in the event of an attack.

The perception of ambivalence is lower for factors considered “purely harmful”, such as the intentional destruction of heritage. This suggests that such threats are clearly perceived in their negativity by managers. However, security planning in these scenarios, particularly in crowded places, requires specific strategies that go beyond the protection of the physical asset to include the management of panicked crowds and security procedures. Site protection and the creation of “safe zones” for cultural heritage in conflicts can be considered, but do not elaborate on crowd management for the safety of people in such scenarios, except implicitly by offering refuge in a “safe zone” if present.

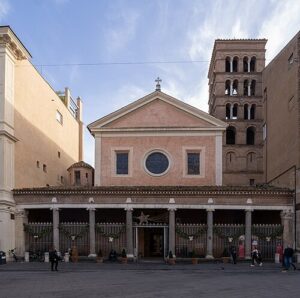

Specific challenges for cities and cultural sites

World Heritage cities present peculiar dynamics. City managers are significantly less likely to perceive various factors as harmful than other types of sites (cultural landscapes, religious sites and others). However, cities are the most affected by issues such as construction and commercial development. Iconic cities such as Venice, Barcelona and Edinburgh have seen the emergence of “anti-tourism” movements due to conflict between residents and tourism growth policies. Specific cases such as Dubrovnik, Seville, Bruges and Florence highlight the negative impacts of urban tourism.

This high-density urban context, often characterised by historical infrastructure less suited to managing massive flows and limited public spaces, becomes particularly fragile in an emergency. The combination of a high density of residents and tourists, concentrated in sensitive historical areas, poses enormous challenges for evacuation planning, access to emergency services and the protection of gathering places (including GLAMs).

Overtourism poses significant challenges not only to the preservation of cultural heritage but also to the safety of people in high-density urban heritage areas and GLAM institutions. As professionals managing these sites, it is crucial to integrate comprehensive safety planning with tourism and urban management to address the complex risks arising from large visitor flows.

Urban Scale Safety Measures

Among the more general measures to be observed on an urban scale, those with the greatest impact are:

- Integrated Urban and Tourism Planning

Safety planning must be embedded within broader urban and tourism strategies, ensuring that infrastructure supports both everyday life and emergency scenarios. This includes:- Clear, well-marked evacuation routes that accommodate large crowds without bottlenecks.

- Designated safe assembly points that are easily accessible and equipped to handle mass gatherings during emergencies.

- Coordination with local emergency services to guarantee rapid access to historic urban cores often characterized by narrow streets and fragile infrastructure.

- Crowd Density Management

Implementing visitor caps and timed entry systems can prevent overcrowding in sensitive areas, reducing risks of accidents and facilitating orderly evacuation if needed. Urban authorities should also promote dispersal strategies, encouraging visitors to explore less congested neighborhoods and off-peak times to alleviate pressure on iconic sites. - Infrastructure Adaptation and Enhancement

Upgrading urban infrastructure is essential to improve safety and resilience:- Enhancing public transport to reduce congestion.

- Improving waste management and sanitation to maintain hygiene during peak tourist seasons.

- Installing surveillance and monitoring systems for real-time crowd management and threat detection.

- Community Engagement and Communication

Local residents should be actively involved in safety planning to ensure their needs are balanced with tourism growth. Clear communication channels must be established to inform both residents and visitors about safety protocols and emergency procedures.

Safety Measures for GLAM Sites

As regards individual buildings, for which measures to mitigate the risks of overcrowding are normally foreseen, a list of the most immediate measures can be the following:

- Visitor Flow Control and Monitoring: GLAM institutions should adopt advanced visitor management systems using digital ticketing and real-time monitoring to control the number of visitors inside at any given time, preventing overcrowding that can hinder evacuation and increase risk during emergencies.

- Emergency Preparedness and Training: staff must be regularly trained in emergency response, including crowd management, evacuation procedures, and first aid. Drills should simulate scenarios involving large visitor numbers to ensure readiness

- Physical Safety Infrastructure: creation of “safe zones” within GLAM sites where visitors can be directed during emergencies, especially in case of intentional threats or natural disasters.

- Technological Integration: leveraging technology such as visitor flow analytics, automated alerts, and digital signage can enhance situational awareness and guide visitors safely during peak times or emergencies.

- Sustainable Architectural Interventions: adaptive reuse and sensitive architectural modifications can improve safety without compromising heritage values. For example, introducing green infrastructure and improving accessibility can both protect the site and enhance visitor experience while mitigating overtourism pressures.

Conclusions

The results of the sources highlight that, although the ambivalence in managers’ perceptions is greater for tourism, factors such as transport infrastructure, land conversion and renewable energy also present these ambiguous characteristics. It is therefore essential to adopt a holistic and complex assessment. For managers and professionals working at local level in heritage sites or areas with a high tourism vocation, it is recommended to:

- Recognize complexity: tourism is a resource, but its negative impacts, including those on safety in case of emergency, cannot be overlooked. It is essential to balance the benefits with the risks.

- Integrated Planning: perceptions vary according to the characteristics of the site and its location. Risk management strategies must be specific to the urban or landscape context, taking into account the capacity for adaptation. Planning for the safety of people must be integrated with tourism and urban planning, considering evacuation routes, safe assembly points and effective warning systems that can also operate in the presence of large crowds.

- Flow Management: Overcrowding is a real problem. Developing appropriate visitor management plans is crucial to meet the needs of both the site and the local community and stakeholders. Better distribution of visitors in time and space can reduce vulnerability.

- Education and Information: Heritage managers are in a privileged position to assess threats and benefits. Supporting their continuous education and ensuring that information on risks is shared with all stakeholders, including tourism operators and visitors, is essential.

The protection of heritage and the safety of citizens require joint efforts at international and national levels. At the local level, this translates into the need for close collaboration between administrators, site managers, law enforcement, civil protection, tourism operators and residents.