Rebuilding an Heritage Canadian Village with Fire-Resilient Principles

On June 30, 2021, during a record-breaking heat dome, the Village of Lytton, British Columbia (Canada) — home to about 250 residents on traditional Nlaka’pamux Nation territory—ignited in under 30 minutes, becoming Canada’s most destructive urban-interface wildfire event to date.

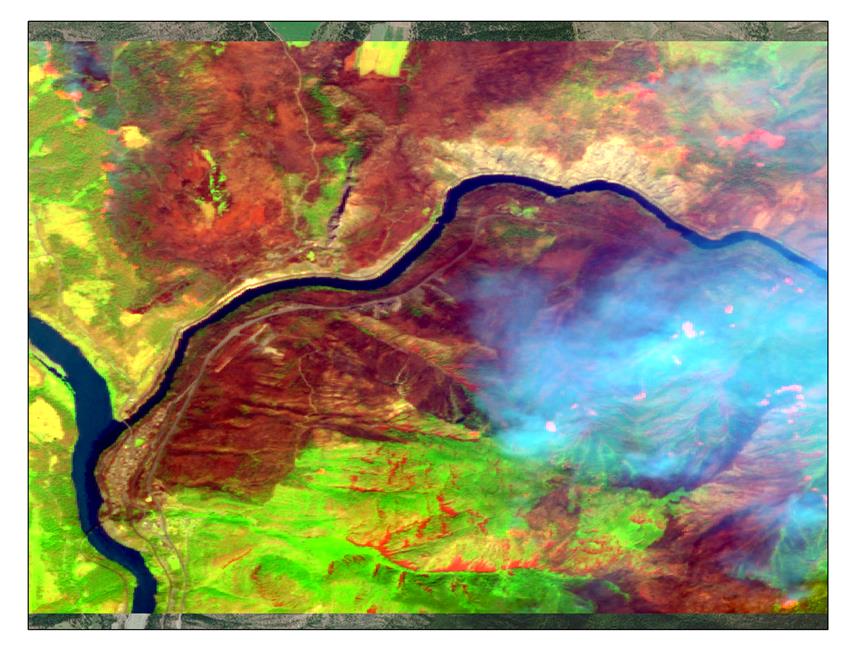

The Lytton Creek Fire erupted on June 30, 2021, just south of the Village of Lytton, British Columbia, amid a historic heat dome that pushed temperatures to 49.6°C—the hottest ever recorded in Canada—coupled with extreme drought and gusty winds. It rapidly escalated into a catastrophic wildland-urban interface (WUI) event, destroying about 90% of the village’s 350 structures (112 primary buildings in the village alone), plus dozens on adjacent Nlaka’pamux First Nations reserves (Klickkumcheen IR 18 and Klahkamich IR 17).

Timeline and spread of the 2021 fire

- Fire discovered around 4:38 PM; within 1 hour, embers and surface fire sparked widespread ignitions along community perimeters.

- By 6:00 PM (under 1.5 hours in), over 20 homes and businesses burned simultaneously, overwhelming any structure protection capacity.

- Evacuation orders hit ~1,000 residents (village and reserves) amid chaos; two civilians died, with others initially unaccounted for but later located.

- Fire grew to 83,000+ hectares before containment in early August; highways, rail lines, and utilities damaged.

Causes and investigations

Lightning was ruled out; early suspicion fell on a CN Rail train (hot brakes or track work sparks), but the Transportation Safety Board found no conclusive evidence after examining rail activity. Post-fire probes emphasize climate-amplified conditions: “extreme but not exceptional” for the region, with embers driving structure-to-structure spread in a densely packed, dry-fueled settlement. Insured losses topped $78 million CAD.

Heritage and cultural impacts

Lytton, on unceded Nlaka’pamux territory with 8,000+ years of Indigenous history, lost key assets: the Lytton Chinese History Museum (1,600 artifacts, archives gone; ~200 recovered later by volunteers), Lytton Museum and Archives (some singed magazines survived), and community buildings tied to First Nations and settler heritage. St. Barnabas Anglican Church sustained minor damage. Post-fire floods/landslides compounded losses on reserves.

Over 90% of its 350 structures, including historic homes, a museum, and community buildings tied to 8,000+ years of Indigenous history, were lost in a firestorm fueled by 49.6°C temperatures and extreme drought.

A model of resilience

Four years after the fire, as of December 2025, federal investments are transforming recovery into a model of resilience.

A recent announcement details $10+ million for net-zero, fire-resistant public infrastructure: a multi-use community hub, cultural museum, market/festival space, and integrated fire/emergency services centre using mass-timber construction, ember-resistant cladding, and FireSmart landscaping. This builds on the provincial Lytton Homeowner Resilient Rebuild Program, which offers grants to homeowners opting for fire-resilient (or fire-resilient + net-zero) designs, enforcing checklists like non-combustible roofs and defensible space.

A key tension emerged from heritage law: mandatory archaeological surveys under BC’s Heritage Conservation Act uncovered artifacts spanning millennia, delaying private rebuilding by months and imposing costs up to $20,000 per lot—frustrating residents but embedding cultural value into zoning and design.

Post-fire reports emphasize the blaze as “extreme but not exceptional,” urging WUI communities to normalize FireSmart measures preemptively.

FireSmartBC (a provincial initiative aimed at reducing the risk of wildfire damage to homes, communities, and forests) and ICLR reports highlight ember vulnerability in WUI zones, urging preemptive defensible space, non-combustible materials, and community drills—principles now baked into Lytton’s 2025 resilient rebuild. Heritage recovery stressed salvaging amid ruins, while archaeology delayed but enriched zoning.

Lessons for heritage fire risk managers

Prioritize resilient reconstruction over speed; integrate archaeology early as a design driver; link funding to verified standards. Lytton’s path shows how disaster can catalyze higher baselines for historic fabric in fire-prone valleys.