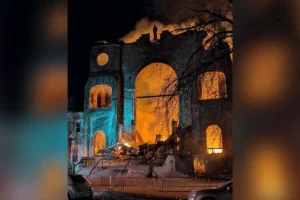

Victorian Mansion demolished by Fire in the UK

Late on the night of 5 October 2025, Shotley Park in County Durham—once a grand Victorian mansion and latterly a residential care home—was heavily damaged by a major blaze, leaving the structure “practically demolished.” The building is Grade II listed under the National Heritage List for England.

The Significance of Grade Listing

In the UK, cultural heritage buildings are categorized into listing grades to reflect their relative architectural and historic importance, primarily Grade I, Grade II*, and Grade II. The criteria used to assign these grades are based on architectural interest, historic interest, and other factors.

Key Features of Grade I Listed Buildings

Grade I listed buildings are of exceptional interest and are sometimes considered to be of international significance. Approximately 2.5% of all listed buildings are designated as Grade I. These buildings often serve as iconic landmarks, showcasing outstanding architectural design, decoration, or craftsmanship. Examples include renowned cathedrals and historically significant structures.

Architectural interest in Grade I listed buildings encompasses their importance in design, decoration, craftsmanship, engineering innovation, and plan forms. Historic interest in Grade I listed buildings lies in their ability to illustrate crucial aspects of the nation’s social, economic, cultural, or military history. Additionally, these buildings often hold strong associations with nationally important individuals or events.

Key Features of Grade II Listed Buildings

Grade II listed buildings are of national importance but are more common or less exceptional than Grade I listed buildings. These buildings are considered of architectural interest, which may include design, techniques, and artistic distinction, although these are generally less rare or iconic compared to Grade I.

Historic interest similarly includes social, economic, or cultural significance, but at a level below the exceptional nature required for Grade I. Buildings classified as Grade II often include houses, local landmarks, or other heritage assets with noteworthy historic or architectural character.

Additional Notes on Listing

Grade II* is an intermediate category for particularly important buildings that exceed special interest but fall short of Grade I. Listings encompass the entire building, including interiors, fixtures, and structures within its curtilage (land associated with the building).

The age of a building plays a significant role in listing decisions. Most buildings before 1700 and many before 1840 are listed; post-1840 buildings are selected more judiciously. Group value, where buildings contribute to a historic or architectural unity (such as terraces or squares), also influences the listing decision. The state of repair of a building is generally not a consideration for listing purposes.

This system aims to protect buildings of national importance with varying levels of significance, ensuring their preservation for future generations while recognizing different degrees of architectural and historic value.

In practical fire service terms, the listing means that any firefighting, salvage, or demolition decisions will attract heightened scrutiny concerning Fire spread control vs heritage conservation, Salvage priority of historic fabric and demolition or partial opening only as last resort, and with consultation (if possible) with heritage bodies

The listing also signals that the building likely included original or historic fabric (masonry, decorative elements, joinery) that could be vulnerable to fire, water, thermal stress, or collapse.

In this case, the record for Shotley Park describes it as an “House, now children’s home. 1842 … late C19 and c.1903 additions … sandstone ashlar, with Welsh slate roof. Main house 2 storeys, 3 bays … set-back 2-storey right extensions … lower additions in front of each extension.”

Architecture, Building Materials & Fire Behaviour Considerations

Thus, the building was composed of high-quality masonry (sandstone ashlar) with slate roofing. The listing description underscores that this was not a purely timber-framed “historic” house in the medieval sense, but a Victorian-era mansion using robust stone, with later additions, which may have mitigated or localized some fire risk—but also created complexity in fire behaviour across additions and junctions.

From the listing and historical descriptions, we can infer key features that would influence both fire progression and firefighting:

- Sandstone ashlar masonry walls

- Likely Behavior / Vulnerabilities:

- Good thermal mass, high fire resistance, non-combustible.

- May crack, spall, or delaminate under severe heat or rapid cooling.

- Firefighting Implications:

- Likely Behavior / Vulnerabilities:

- Welsh slate roof

- Timber structural members / roof timbers / floor joists (typical of Victorian houses)

- Likely Behavior / Vulnerabilities:

- Firefighting Implications:

- Extensions and additions (late 19th, c.1903, and later glass-roofed additions)

- Likely Behavior / Vulnerabilities:

- Firefighting Implications:

- Fire can bridge between interconnected wings, endangering more areas.

- Special attention to monitoring and containing fire at these interfaces.

- Glazed atria, conservatories, pent glass structures (later additions)

- Likely Behavior / Vulnerabilities:

- Firefighting Implications:

- Rapid vertical flame spread is possible; risk of glass shattering and convection flows.

- Must address access issues and be prepared for sudden changes in compartmentalization.

- Interior finishes, historic joinery

- Likely Behavior / Vulnerabilities:

- Firefighting Implications:

- Intense compartment fires; challenge to preserve historic interiors.

- Fire protection systems may be absent or inadequate; risk to valuable artifacts from direct flame and water or smoke damage

Fire Timeline, Response & Observations

According to the media report, the fire is believed to have originated around 10:20 pm, at its peak. At that time, five fire engines were deployed. By morning, the structure had been described as “practically demolished.” The cause of the fire is currently under investigation.

Those facts suggest a rapidly developing fire, possibly already well advanced before discovery or by the time the first crews arrived. Given the building’s size, multiple wings, and known vacant status, fire escalation inside concealed voids or wings may have progressed undetected until breaching or collapse occurred.

Possible Causes & Hypotheses (to Support Investigation)

While we cannot conclude cause, here are plausible ignition scenarios or contributing factors a fire‑investigation team should consider, especially in the context of heritage buildings left vacant:

- Electrical fault / wiring residual systems. Though vacant, some residual or legacy electrics (e.g. old wiring, residual circuits, security lighting) may still remain. If tampering or rogue power supply was present (unauthorised access), an electrical fault could start a fire.

- Arson / vandalism / wilful ignition. Abandoned and vandalised heritage buildings are unfortunately prime targets.

- Trespass, squatter activity, mischief fires could be initial triggers.

- Accelerants or external ignition (e.g. discarded cigarette, incendiary device) must be considered, particularly given the building was already unoccupied.

Deliberate fire for “clearance” or insurance fraud. A scenario investigators should always include is setting fire intentionally to clear the site or prematurely degrade so that later redevelopment is simplified.

Smoldering ignition in combustible debris or stored materials. The building may have housed residual furniture, stored materials, wood debris, or flammable rubbish which, if illegally stored or dumped, could self-ignite or be ignited by careless human activity (for instance, from smoking).

Lessons & Key Fire Professional Takeaways

Vacancy risk in heritage buildings poses a significant hazard. When historic buildings lose their functional use, they often increase their fire risk due to neglect, vandalism, deterioration, and the absence of routine inspection and maintenance.

Heritage buildings exhibit a paradoxical nature. While their strong masonry shells protect cored spaces, the interior timber and junctions are vulnerable. Fire control must strike a balance between conservation concerns (avoiding excessive openings) and firefighter safety and suppression effectiveness.

Rapid fire spread through junctions and voids is a concern. Later additions and wings, often constructed differently or with less weight, can act as conduits for fire. In such cases, crews should anticipate unexpected fire “jumping” between wings.

Pre-incident planning and protection are crucial in at-risk vacant historic buildings. Risk mitigation measures, including security, internal compartmentalization, debris removal, and fire detection, are vital. Fire services and heritage agencies should collaborate to monitor vulnerable sites.

Incident command must prioritise heritage value over safety and collapse risk. While it may be necessary to sacrifice certain parts of the building to protect life, efforts should be made to preserve irreplaceable heritage elements whenever feasible.

Early forensic cooperation is critical in heritage fire losses, as they are irreversible. Investigative teams should integrate fire, structural, heritage, and law enforcement expertise from the outset.