Review and Critique of UNESCO’s Fire Risk Management Guide

In a previous post (Fire Risk Management Guide (2024) Protecting Cultural and Natural Heritage from Fire) , this platform has briefly described the 2024 Guide aimed at helping heritage site managers, policymakers, emergency responders, and communities understand, prevent, and respond to fire risks threatening cultural and natural heritage worldwide.

In the following text, additional considerations are presented to initiate a discussion regarding the necessity of enhancing the content of the significant work commissioned by UNESCO.

The absence of automatic fire suppression systems poses a risk?

One of the central issues in the guide is the way it frames the absence of automatic fire suppression systems as a “risk.” However, this wording is conceptual: risk arises from hazards, such as ignition sources, interacting with vulnerabilities, such as combustible materials, poor compartmentation, or human error.

The non-existence of a specific protective system cannot itself be classified as a risk. It is more accurately a vulnerability or a factor that increases susceptibility to damage.

A more precise formulation would therefore be to describe this as “the absence of automatic suppression systems increases vulnerability to uncontrolled fire growth,” rather than labelling it a risk in its own right. For instance, the NFPA 551: Guide for the Evaluation of Fire Risk Assessments makes a clear distinction:

- Hazard: A condition with the potential to cause harm (e.g., ignition sources, combustibles).

- Risk: The probability of a fire event occurring combined with its potential consequences.

The absence of an automatic suppression system does not meet NFPA’s definition of a hazard or a risk on its own. Instead, it could be treated as a vulnerability (susceptibility of people, property, or systems to damage or loss when exposed to hazards or contributing factor that increases the severity of consequences once a hazard manifests).

For example, both NFPA 550: Guide to Fire Safety Concepts Tree and NFPA 551 use the conceptual model of hazards (ignition sources, fuel loads) interacting with vulnerabilities (flammable interiors, inadequate protection) to generate risk. A missing suppression system thus could be considered a vulnerability because it removes a layer of defence, but it does not itself create risk independently.

This interpretation aligns with the general structure of fire risk assessments: the absence of suppression is a contributing factor to uncontrolled fire growth and damage, but risk only emerges when hazards and vulnerabilities interact.

The actual role of suppression systems

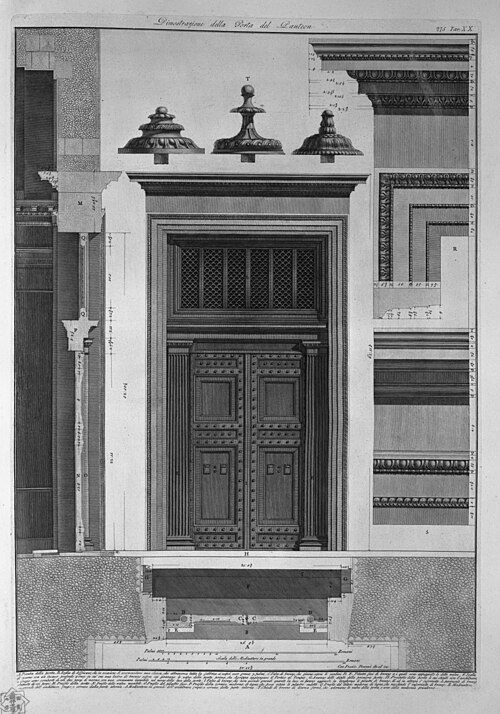

The Guide appears to overemphasise active suppression systems such as sprinklers, water mist, or gas systems. In heritage contexts, these systems often face practical challenges due to architectural or conservation restrictions, high installation and maintenance costs, and the potential for secondary damage to collections. A revised guide would ideally rebalance this emphasis, placing greater weight on passive protective measures such as compartmentation, material treatment and management, and organisational strategies like training and emergency planning.

While the Guide acknowledges human and organisational aspects, it places less significance than international reference frameworks (UNESCO, ICCROM), which explicitly elevate these factors to a primary concern in cultural heritage risk management. UNESCO and ICCROM recognise human and organisational aspects as central to cultural heritage safety. Notably:

- UNESCO (Managing Disaster Risks for World Heritage, 2010) underscores that disasters encompass not only physical hazards but also institutional capacity, preparedness, training, and community involvement. It emphasises that risk management must encompass organisational structures, governance, and human resources, not solely technical protection.

- ICCROM (Risk Management for Cultural Heritage, 2016) further emphasises the significance of human and organisational factors.

Their approach highlights:

- Staff training and awareness

- Emergency planning and preparedness drills

- Organisational culture and decision-making structures

- The role of human error, inadequate preparedness, or weak institutional frameworks in exacerbating vulnerability.

In contrast to the Guide, UNESCO and ICCROM documents acknowledge human and organisational factors as fundamental dimensions of vulnerability and resilience, rather than peripheral considerations.

Negligence in Addressing Secondary Damage

The guide provides only a cursory examination of the risk of secondary damage resulting from suppression systems. This oversight is problematic, particularly for fragile heritage such as manuscripts, frescoes, or historic wooden interiors, where water or chemical damage may equal or even surpass the losses caused by the fire itself.

A revised version of the guide would provide more comprehensive guidance on alternative solutions, including localised mist systems, inert gas suppression, or hybrid approaches that are more compatible with conservation objectives. In particular:

- UNESCO & ICCROM Guidance

- UNESCO, Managing Disaster Risks for World Heritage (2010): stresses that some firefighting measures can themselves cause significant damage, especially to archives, manuscripts, and interiors, and urges balancing protection against both fire and suppression impacts.

- ICCROM, Risk Management for Cultural Heritage (2016): highlights the risks of water and chemical damageas major secondary hazards and advocates exploring technologies “compatible with conservation needs.”

- NFPA Acknowledgment of Water Damage

- NFPA 232 (Standard for the Protection of Records, 2017) explicitly warns that water from sprinklers or fire hoses can be as damaging as fire for documents, manuscripts, and archives. It encourages special protection (e.g., water mist, inert gas systems) in archives and libraries.

- NFPA 909 (Code for the Protection of Cultural Resource Properties, 2021): recognizes that conventional suppression systems may not be appropriate for fragile heritage, and recommends tailored solutions such as clean agents and mist systems.

The Significance of Human and Organisational Factors

While human and organisational factors are acknowledged, their attention is not adequately given. It is crucial to recognise that numerous catastrophic heritage fires have been the consequence of human error rather than technical failures. These errors include disabled alarms, inadequate evacuation procedures, and delayed notification.

A more effective guide would prioritise organisational resilience by recommending mandatory drills, well-defined salvage and evacuation plans, trained cultural first responders, and the involvement of local community volunteers. Iwith specifically reference to UNESCO and ICCROM documents:

- UNESCO’s (2010) Managing Disaster Risks for World Heritage emphasises that disasters encompass not only physical hazards but also institutional capacity, preparedness, training, and community involvement. The document underscores the importance of risk management that encompasses organisational structures, governance, and human resources, not merely technical protection.

- ICCROM’s (2016) Risk Management for Cultural Heritage further emphasises the significance of human and organisational factors.

Also in this instance, it is pertinent to recall that their approach emphasises the following salient aspects:

- Staff training and awareness

- Emergency planning and preparedness drills

- Organisational culture and decision-making structures

- The Role of Human Error, Lack of Preparedness, and Weak Institutional Frameworks in Amplifying Vulnerability

In contrast to the Guide, UNESCO and ICCROM documents recognise human and organisational factors as fundamental dimensions of vulnerability and resilience, rather than peripheral considerations. While the Guide acknowledges these aspects, it places less emphasis on them compared to international reference frameworks (UNESCO, ICCROM), which explicitly elevate these factors to a primary concern in cultural heritage risk management.

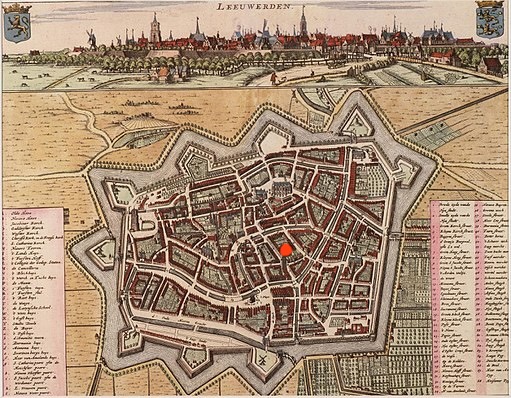

Universal Applicability of the Fire Risk Management Plan (FRMP)

Another limitation of the guide is its assertion of the FRMP’s universal applicability. This framing overlooks the fact that international reference frameworks explicitly emphasise the need to adapt disaster and fire risk management to context. UNESCO’s Managing Disaster Risks for World Heritage underscores the importance of tailoring strategies to the specific characteristics of each property, considering governance structures, heritage type, and available resources to determine what is realistic and effective.

Similarly, ICCROM’s Risk Management for Cultural Heritage acknowledges the absence of a universal method to reduce risks and emphasises that each site’s unique values, vulnerabilities, and capacities must shape the approach. ICCROM’s First Aid to Cultural Heritage in Times of Crisis highlights the necessity of preparedness and response plans adapting to the cultural, social, and institutional context of the community managing the heritage.

These authoritative positions collectively demonstrate that presenting the FRMP process as universally applicable is problematic, as it risks overlooking the diverse realities of heritage sites, ranging from resource-constrained community-managed shrines to living traditions involving ritual fire to conflict-affected regions where institutional frameworks may be absent.

The limitations of a universal FRMP approach become apparent when considering real-world heritage cases. At resource-rich sites such as Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, a comprehensive FRMP with advanced detection, suppression, and compartmentation is both feasible and anticipated.

Conversely, the Kasubi Tombs in Uganda, predominantly constructed of thatch and timber and managed by local communities, rely more effectively on traditional practices and watch systems than on intricate engineering-based plans.

The National Museum of Brazil fire in 2018 illustrates how even where an FRMP might be envisioned, chronic underfunding and inadequate system maintenance can render it ineffective. In contexts of living heritage, such as torchlight festivals in Japan, the risks primarily originate from ritual fire use, where regulation and the dissemination of safe practices are more critical than structural suppression.

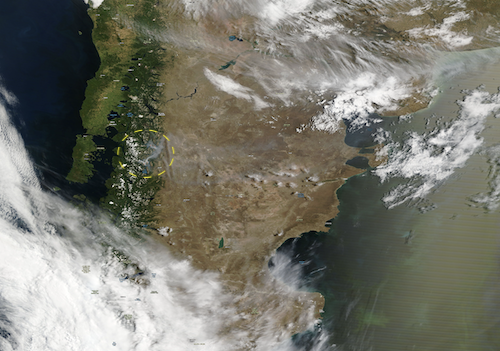

For cultural landscapes, like the UNESCO-listed Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras, wildfire management through vegetation control and community brigades is far more pertinent than compartmentation or sprinklers.

Finally, in conflict-affected regions such as Syria or Ukraine, where governance and infrastructure are disrupted, heritage protection hinges on emergency salvage and improvisation rather than structured FRMPs. These diverse examples underscore that the FRMP process cannot be universally applied across heritage contexts without risking impracticality or ineffectiveness.

- Notre Dame Cathedral (France, 2019): A high-profile, resource-rich site where a formal FRMP (with detection, suppression, and compartmentation) is feasible and anticipated.

- Kasubi Tombs (Uganda, 2010 fire): A community-managed heritage site predominantly constructed of thatch and timber. In this case, traditional practices and local watch systems are more practical than a comprehensive FRMP with advanced fire engineering.

- National Museum of Brazil (2018 Fire): Despite the potential existence of a fire response mechanism (FRMP), chronic underfunding and inadequate maintenance rendered the suppression systems non-operational, demonstrating how resource constraints hinder the universal applicability of FRMPs.

- Sacred Torchlight Festivals in Japan: Risks arise from ceremonial fire usage, where safety relies on social regulation and ritual practice rather than structural fire suppression.

- UNESCO Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras: This cultural landscape necessitates vegetation management and community fire brigades to address wildfire risk, not compartmentalization or sprinklers.

- Heritage sites in Syria or Ukraine (conflict settings): Institutional collapse and security threats prioritise improvisation and emergency salvage over formal FRMPs.

These examples illustrate that FRMPs may be effective for well-funded urban monuments but not for living heritage, landscapes, or conflict-affected sites, which require adapted and context-sensitive strategies.

Are NFPA, ISO, and SFPE Standards universally applicable?

The same observation made above can be repeated with reference to NFPA, ISO, and SFPE Standards. While the Guide draws upon international standards such as NFPA, ISO, and SFPE, it assumes that these standards can be universally applied. However, in practice, their application often clashes with national regulations and preservation policies.

For instance, NFPA 13 mandates automatic sprinkler protection in numerous occupancies with combustible contents, whereas several European countries, including France and Italy, permit heritage buildings to omit sprinklers in favour of alternative measures due to concerns about water damage to historic fabric.

Similarly, the SFPE performance-based design approach, endorsed in ISO 23932, can conflict with jurisdictions such as Japan or Germany, where regulators enforce stringent prescriptive fire-resistance requirements and may reject engineered equivalencies.

These examples demonstrate that while international standards provide valuable guidance, they cannot be directly transplanted across contexts without modification, rendering the guide’s assumption of global applicability problematic. Specifically, the following points highlight the challenges:

- Fire Suppression Requirements: NFPA 13 mandates automatic sprinkler protection in numerous occupancies where combustible contents are present. In contrast, several European national codes (e.g., France, Italy) permit alternative performance-based approaches without sprinklers, particularly in heritage buildings, due to concerns about water damage or preservation of historic fabric. But an UNESCO-listed wooden church in Norway is not mandated by national code to install sprinklers, whereas the NFPA classifies the absence as a deficiency.

- Fire Resistance and Compartmentation: ISO 23932 and the SFPE Fire Safety Engineering Guide promote performance-based fire safety design, including engineered compartmentation and evacuation strategies. In practice, countries like Japan and Germany maintain stringent prescriptive building codes that may prohibit performance-based substitutions unless explicitly authorised by regulatory authorities. But an SFPE performance-based evacuation analysis demonstrating equivalent safety may still be rejected by Japanese authorities due to the local code’s mandate for prescriptive fire-resistance ratings.

- Electrical and Ignition Standards: NFPA 70 (National Electrical Code) employs distinct wiring classifications, circuit protection regulations, and hazardous area requirements compared to IEC/European standards. But an electrical installation deemed code-compliant under NFPA could be deemed unsafe or illegal under EU law, directly impacting fire risk management strategies in heritage sites utilising international teams.

Conclusion

The UNESCO Fire Risk Management Guide (2024) is an important step forward in addressing one of the most pressing threats to cultural heritage. Its holistic and inclusive framework will be valuable to heritage managers worldwide. However, its treatment of risks and vulnerabilities, emphasis on active suppression, and limited attention to human and contextual factors represent notable weaknesses. A more balanced, context-sensitive approach would strengthen its applicability and ensure that the guide better reflects the realities of heritage fire safety management.