A Toolkit for Cultural Heritage by War Risks

Updated January 2026

Introduction

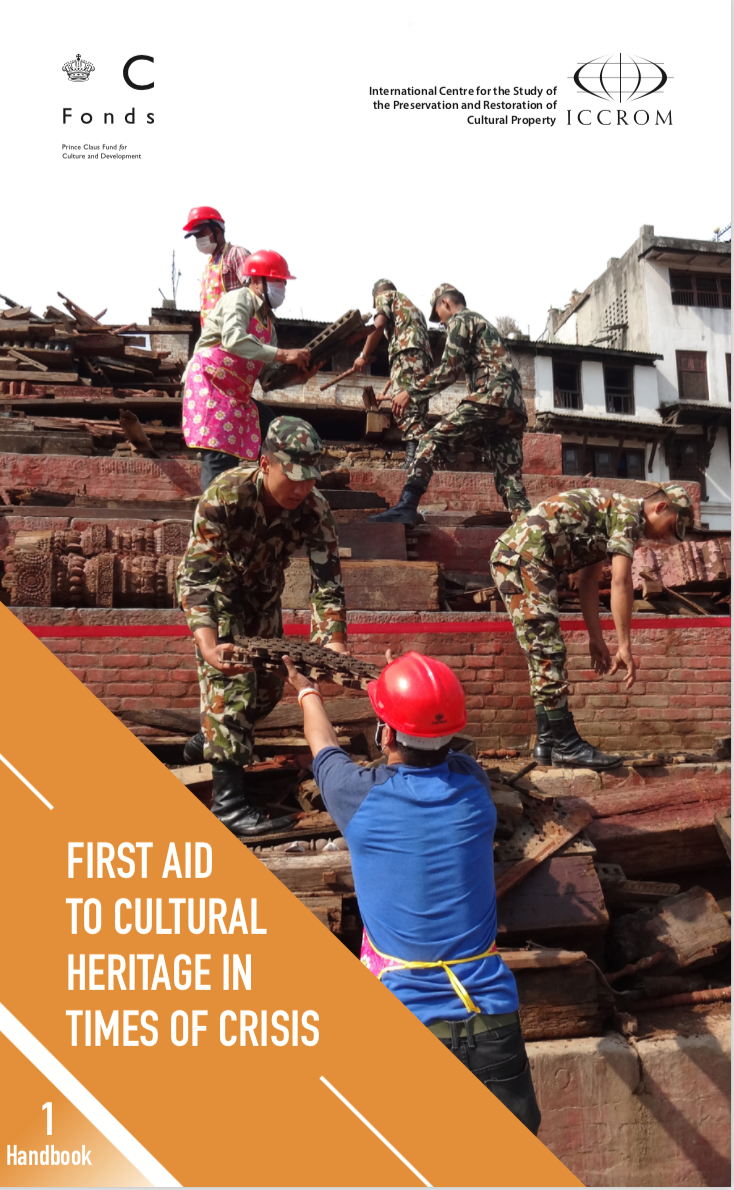

In October 2018, ICCROM (the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property) and the Prince Claus Fund published two groundbreaking documents on “First Aid to Cultural Heritage in Times of Crisis”: a 176-page handbook and a 104-page toolkit. Both publications, authored by ICCROM’s Aparna Tandon and created within the framework of the ICCROM-Prince Claus Fund-Smithsonian Institution collaboration, are aimed at developing capacity in emergency preparedness and response for cultural heritage. They can be downloaded free from the ICCROM website.

The First Aid to Cultural Heritage in Times of Crisis Handbook and Toolkit is the outcome of nearly a decade of field experience gained by ICCROM, and a close partnership among ICCROM, the Prince Claus Fund, and the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative. It has been developed to answer the increasing need for cultural heritage professionals and humanitarians alike to have a reliable and user-friendly reference that integrates heritage safeguarding into emergency and recovery activities, offering standard operating procedures applicable in almost any crisis context.

The urgency of cultural heritage protection in crisis situations

In the dynamic landscape where culture is acknowledged as a driving force for development, the fragility of these gains in the face of disasters is starkly evident. The profound impact of such setbacks on communities underscores the urgent need for a comprehensive approach to safeguard cultural heritage. Amidst the narratives of suffering and loss, however, stories of resilience have emerged, prompting a closer examination of the intricate relationship between cultural traditions and coping mechanisms within the scientific community.

Fires can have devastating consequences on heritage, destroying cultural landmarks, disrupting local communities, and damaging ecosystems. Today, these risks are further exacerbated by climate change and conflicts. Recent years have witnessed a rise in the frequency and intensity of fires, raising alarm about the loss of heritage sites, biodiversity, and traditional knowledge.

A significant challenge lies in the lack of formal inclusion of cultural heritage considerations in most national and local emergency response systems. Yet, firsthand experiences of first responders reveal an inevitable involvement in heritage rescue efforts, driven by a dual concern for local lives and an awareness of the profound role heritage plays in overcoming loss and trauma.

Development of the FAC methodology

Aligned with the belief that culture is a fundamental need, both the Prince Claus Fund and ICCROM have shared a commitment to conserving culture and promoting diversity. Recognizing the pivotal role of communities as primary stakeholders, these organizations collaborated to develop a resource aimed at integrating the voices of the community into the recovery of culturally significant places and objects. This collaborative effort serves as a means to empower communities and enhance their resilience against future disasters.

The urgency of cultural preservation brought about their joint initiative in 2010—the First Aid to Cultural Heritage in Times of Crisis course, which has evolved into the creation of a network of “cultural first aiders” supported by the Prince Claus Fund. The presented handbook and toolkit seek to codify First Aid processes, stimulate further research and activity, and heighten awareness. Recognizing that each emergency offers unique lessons, the creators aim to bridge knowledge gaps through inclusive discussions, representing diverse viewpoints.

Core philosophy and approach

The handbook is focused on simple instructions and case studies which explain what has to be done and how to do it. According to the forewords, the toolkit is “intended to codify the First Aid processes and further stimulate research, activity and awareness”.

Written with the key guiding philosophy of ensuring an inclusive attitude and respect for diversity while at the same time interlocking humanitarian assistance with cultural heritage first aid, this resource provides an essential, ethical framework that will lead to successful outcomes.

The resource has multiple uses: it will help to improve emergency preparedness within cultural heritage institutions, serve as a reference to train others, and act as a guide for planning and implementing coordinated cultural heritage first aid.

The three-phase emergency strategy

The ICCROM website specifies that the emergency strategy of cultural heritage First Aid is based on three phases which collectively lead to early recovery:

Phase 1: Situation analysis

The first phase involves rapid assessment of the emergency context, including:

- Understanding the nature and scale of the crisis

- Identifying affected cultural heritage sites and objects

- Assessing security conditions and access constraints

- Mapping available resources, personnel, and expertise

- Establishing communication channels with stakeholders

- Coordinating with emergency responders and humanitarian agencies

This phase provides the foundation for informed decision-making and prioritization of response efforts.

Phase 2: Post-event, on-site damage and risk assessment

The second phase focuses on systematic evaluation of cultural heritage conditions:

- Conducting detailed damage assessments of buildings, collections, and intangible heritage

- Identifying immediate threats (structural instability, water damage, fire hazards, looting risks)

- Prioritizing intervention needs based on vulnerability and significance

- Documenting damage through photography, sketches, and written reports

- Evaluating safety conditions for personnel and public access

- Determining required resources and expertise for stabilization

This assessment informs the development of targeted stabilization strategies.

Phase 3: Security and stabilisation

The final phase implements protective measures to prevent further deterioration:

- Securing sites against looting, vandalism, and unauthorized access

- Stabilizing structures at risk of collapse

- Protecting collections from environmental damage (water, fire, pests)

- Implementing temporary repairs to prevent progressive damage

- Evacuating and relocating vulnerable objects when necessary

- Establishing monitoring systems for ongoing risk management

- Planning for longer-term recovery and restoration

These three phases include workflows and procedures that resemble those followed by emergency responders and humanitarian aid professionals, making in-field coordination possible.

Detailed toolkit contents

The toolkit is rich with checklists, templates, and tips that can be customized to any situation. Specific contents include:

Assessment tools

- Rapid Damage Assessment Forms: Templates for quickly documenting heritage damage in field conditions

- Risk Evaluation Matrices: Tools for prioritizing intervention needs based on threat level and heritage significance

- Structural Stability Checklists: Guidelines for assessing building safety before entry

- Collection Condition Reports: Standardized formats for documenting object damage

Planning and coordination templates

- Emergency Response Plans: Frameworks for developing site-specific emergency procedures

- Stakeholder Mapping Tools: Templates for identifying and coordinating with relevant actors

- Resource Inventories: Checklists of equipment, materials, and expertise needed for response operations

- Communication Protocols: Guidelines for establishing effective information sharing among responders

Stabilization guides

- First Aid Procedures by Material Type: Specific instructions for stabilizing paper, textiles, wood, metal, stone, ceramics, and other materials

- Temporary Protection Measures: Guidance on emergency weatherproofing, fire protection, and security measures

- Salvage Priorities: Decision-making frameworks for evacuation and relocation of collections

- Safe Handling Techniques: Illustrated instructions for moving damaged objects

Documentation resources

- Photography Guidelines: Standards for documenting heritage damage and response activities

- Reporting Templates: Formats for communicating assessment findings to authorities and stakeholders

- Before-and-After Comparison Tools: Methods for tracking intervention outcomes

- Digital Documentation Protocols: Guidance for creating accessible digital records

Context-specific adaptations

- Conflict Zone Considerations: Additional safety protocols and coordination mechanisms for war-affected areas

- Natural Disaster Variations: Tailored approaches for floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, and fires

- Resource-Constrained Contexts: Alternatives using locally available materials and low-tech solutions

- Cultural Sensitivity Guidelines: Frameworks for respecting community values and traditional practices

Fire risk in conflict zones: a critical threat to cultural heritage

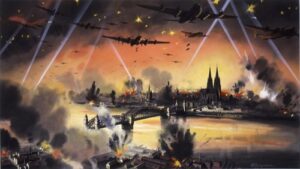

While natural disasters pose significant risks to cultural heritage, armed conflicts create particularly complex fire threats that combine direct targeting, collateral damage, and breakdown of protection systems.

The amplified fire risk in war zones

Conflict situations dramatically increase fire risks to heritage sites through multiple mechanisms:

1. Direct military action

- Deliberate targeting of cultural sites as tactical or symbolic objectives

- Incendiary weapons causing intense, rapidly spreading fires

- Explosive ordnance damaging fire protection systems and creating ignition sources

- Artillery and aerial bombardment compromising structural integrity and exposing combustible materials

2. Breakdown of fire protection infrastructure

- Damage or destruction of fire detection and suppression systems

- Disruption of water supply for firefighting

- Inability to maintain electrical systems, increasing short-circuit fire risk

- Evacuation of trained personnel, leaving sites unmonitored

3. Secondary conflict-related risks

- Looting and vandalism including arson

- Improvised heating and cooking by displaced populations sheltering in heritage buildings

- Military occupation introducing flammable materials (fuel, ammunition, equipment)

- Loss of security allowing accidental fires to go undetected and unreported

4. Delayed response capacity

- Fire services unable to access sites due to active combat or minefields

- Lack of firefighting equipment and supplies due to supply chain disruption

- Reluctance of international assistance to enter conflict zones

- Prioritization of civilian emergencies over heritage protection

Recent conflict-driven heritage fires: lessons from Ukraine and Syria

Ukraine (2022-Present)

Since the Russian offensive began on February 24, 2022, the damage or destruction of at least 127 culturally important sites have been verified by UNESCO, though Ukrainian reports mention 284 heritage sites. Several theaters, museums, churches, and other historical buildings in attacked cities have had their windows shattered, their walls laced with bullet holes, or have entirely crumbled to pieces from shelling.

UNESCO reported that a total of 29 religious sites, 16 historic buildings, four museums, and four monuments have been confirmed as damaged within Ukraine. The sites include more than a dozen in the eastern Kharkiv region that has been intensely hit by Russian fire, including various churches and modern heritage sites.

At the outset of the Russian invasion, Ukrainian cultural officials and leaders responded quickly to protect facilities and collections from shelling and bombing. UNESCO arranged online meetings bringing together Ukrainians with European and American counterparts to discuss needs, resources, and responses. The Switzerland-based Aliph Foundation responded adroitly, quickly devoting several million dollars for packing and shipping supplies, fire extinguishers, and other materials to scores of museums and institutions, working closely with Ukrainian colleagues to improve collection storage facilities.

Heritage for Peace started to assist heritage workers in Ukraine in their efforts for the protection of rich cultural heritage in Ukraine since March 2022. Their guide uses a Risk Informed Approach derived from the Disaster Cycle, covering Prevention and Mitigation, Response and Recovery, and Salvage of historic buildings, including wooden buildings and building-integrated artworks, under threat of fire in a war. There is a focus on substitutes for professional materials and equipment, including suggestions for materials that can be sent to Ukraine.

Syria (2011-Present)

The Syrian conflict has resulted in catastrophic heritage losses, with numerous World Heritage Sites damaged or destroyed. Fire has played a significant role in heritage destruction, including:

- Deliberate burning of historic souks and markets in Aleppo

- Fire damage to archaeological museums and collections

- Destruction of wooden architectural elements in historic mosques and churches

- Loss of manuscript collections in library fires

Fire protection strategies in conflict zones

The ICCROM toolkit provides critical guidance adaptable to conflict scenarios:

Before conflict (prevention and mitigation)

- Emergency evacuation planning for movable heritage

- Documentation of collections and sites for post-conflict recovery

- Establishment of remote monitoring systems

- Pre-positioning of fire suppression equipment and materials

- Training of local personnel in basic firefighting techniques

- Marking of heritage sites with protected status emblems (Blue Shield)

During active conflict (damage limitation)

- Temporary fire protection measures using locally available materials

- Coordination with military forces to avoid heritage sites as targets or bases

- Community engagement to maintain vigilant monitoring when official protection fails

- Rapid damage assessment when access windows become available

- Prioritized salvage of most vulnerable and significant objects

Post-conflict (stabilization and recovery)

- Immediate fire risk assessment of damaged structures

- Removal of explosive remnants that could cause fires

- Restoration of water supply and fire protection systems

- Rehabilitation of fire services capacity

- Documentation of conflict-related damage for accountability and reconstruction

Practical application examples

Example 1: museum collection evacuation in conflict zone

Scenario: A regional museum housing significant ethnographic collections faces imminent threat from advancing conflict.

Application of FAC methodology:

- Phase 1 (Situation Analysis): Museum director assesses that facility evacuation is necessary within 48 hours. Uses FAC stakeholder mapping tools to identify available trucks, secure storage locations in safer regions, and coordination with international heritage organizations.

- Phase 2 (Risk Assessment): Employs FAC prioritization matrix to identify most vulnerable/significant items (flammable textiles, irreplaceable manuscripts, ceremonial objects). Documents current condition through photography protocol provided in toolkit.

- Phase 3 (Stabilization): Following FAC packing guidelines, wraps objects using available materials (clean cotton sheets, cardboard, plastic sheeting). Uses toolkit evacuation checklist to ensure proper documentation, labeling, and inventory control during transport.

Outcome: 85% of priority collection successfully evacuated before facility damaged in shelling. FAC documentation enables proper storage, monitoring, and eventual return of objects.

Example 2: post-earthquake fire prevention in historic center

Scenario: Major earthquake damages historic wooden buildings; risk of fire from broken gas lines and electrical systems is extreme.

Application of FAC methodology:

- Phase 1 (Situation Analysis): Heritage emergency team conducts rapid survey using FAC damage assessment forms, mapping buildings at greatest risk of collapse or fire. Coordinates with fire services and utilities companies using communication protocols from toolkit.

- Phase 2 (Risk Assessment): Employs FAC structural stability checklists to determine which buildings can be safely entered for assessment. Uses risk evaluation matrix to prioritize intervention based on structural vulnerability, fire load, and heritage significance.

- Phase 3 (Stabilization): Implements temporary fire protection measures from toolkit: removes combustible debris, disconnects damaged electrical panels, posts fire watches, distributes portable extinguishers. Works with community volunteers trained using FAC guidelines to maintain 24-hour monitoring.

Outcome: No major fires occur during critical first week post-earthquake. Systematic approach enables efficient allocation of limited fire protection resources to highest-priority sites.

Example 3: flood-damaged archives salvage operation

Scenario: Catastrophic flooding inundates national archives; thousands of historical documents at risk of mold and deterioration.

Application of FAC methodology:

- Phase 1 (Situation Analysis): Archives staff uses FAC templates to quickly inventory affected collections, estimate quantities, and determine required resources (dehumidifiers, fans, freezers, packing materials).

- Phase 2 (Risk Assessment): Employs collection condition reports to prioritize salvage (unique manuscripts before duplicate prints, bound volumes before loose papers). Documents damage extent for insurance and donor reporting.

- Phase 3 (Stabilization): Follows FAC material-specific first aid procedures: air-drying for coated papers, freezing for severely wet documents, interleaving for damp books. Uses toolkit safe handling techniques to prevent further damage during recovery operations.

Outcome: Over 80% of unique archival materials successfully stabilized and recovered. Standardized FAC approach enables rapid training of volunteer salvage teams.

Adapting the toolkit to different conflict contexts

The true strength of the ICCROM First Aid to Cultural Heritage toolkit lies in its adaptability to diverse emergency contexts. While the core methodology remains consistent, effective application requires context-specific modifications.

High-intensity combat zones

Adaptations needed:

- Integration with military coordination mechanisms.

- Abbreviated assessment procedures that can be completed in short time windows when access is possible

- Remote monitoring technologies (satellite imagery, drone surveillance) to supplement physical assessment

- Pre-positioned supplies and equipment rather than relying on emergency delivery

- Decentralized decision-making authority when communication with central authorities is disrupted