Historic Heritage Under Assault: The Erasure of Armenian Churches

The systematic destruction of historical and cultural heritage sites, particularly Armenian churches and monasteries, in Western Armenia (now predominantly located in Eastern Anatolia), historically known as the Armenian highlands, constitutes a profound and ongoing loss to the world’s cultural heritage. Such intentional devastation, also perpetrated in Nagorno-Karabakh, underscores the gravity of this issue.

This cancellation is not simply an unfortunate consequence of conflict or negligence, but is deeply intertwined with a policy of denial and a continuous process of ethnic cleansing. This is a persistent and current problem, as evidenced by articles published in 2025 that continue to document these schemes.

The cancellation of the Armenian heritage in Türkiye’s Western Armenia

Historically, since 1915 there has been a deliberate and systematic effort to destroy Armenian material culture in what was Western Armenia.

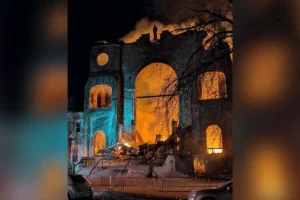

- Targeted destruction and reuse. Churches and monasteries have been specifically targeted for total destruction. The province of Bitlis, for example, which included the Moush region, housed 510 churches and 161 monasteries in 1914, but only a handful remained in Armenian hands outside of Istanbul after the genocide. These buildings have been demolished, left in ruins, have become the target of treasure hunters or have been converted into mosques, prisons, barns or stables. Armenian names and inscriptions have been removed, and public authorities have attributed their origins to Turkish or Seljuk heritage. The 13th-century Armenian church of Surp Minas, in the Zadar district of Sivas province, has been repeatedly the target of excavations and associated destruction by illegal treasure hunters, with the church cemetery recently damaged during excavation work and human bones scattered on the cemetery grounds, as reported in July 2025. Although the church of Surp Minas survived thanks to its conversion into a mosque, preventing its complete demolition as happened to other churches destroyed by villagers in search of gold, today only rubble, stone fragments, a symbol of the cross and an Armenian inscription indicating the date of foundation remain.

- De-Ethnicization. This policy of destruction and erasure constitutes a fundamental pillar of the De-Ethnicization. The non-Muslim heritage, including the Armenian heritage, has been largely unprotected and de-ethnicized, often referred to as “Byzantine” or “Ottoman” to abstract its specific Armenian origins and eliminate references to its history. Even sites that have undergone conservation interventions, such as the church of Akhtamar or the ancient city of Ani, are de-politicized and used to promote narratives of peaceful coexistence or generic historical wealth, instead of recognizing their distinct Armenian origin. The Ministry of Culture, for example, refused to reposition a cross on the church of Akhtamar, and Christian functions are only allowed once a year. It is estimated that about 2,000 Armenian churches were destroyed in western Armenia after 1915, with only a handful remaining today.

- Tourism of faith” and commodification without recognition. The state program of “tourism of faith” (inanç turizm ), started in the 1990s, aimed to economically develop peripheral regions by attracting religious travelers to valuable sites, including Christian ones. However, this has often involved containing the “disrupting potential” derived from the recognition of the Armenian heritage, framing it in an Ottoman narrative of multi-religious cosmopolitanism and imperial tolerance. Ethnographic research conducted between 2012 and 2015 and published in January 2025 revealed that local residents in regions such as Moush showed general indifference to the moral implications of the commercialization of Armenian material remains, considering it largely an economic opportunity. This indifference is seen as a trace of the historical experience of having benefited from the complete expropriation that took place in 1915. Although there were fantasies to develop sites such as the Meryem Ana Church, the Surp Garabet Monastery and the Arakelots Monastery for Armenian pilgrims, these projects remained largely unfulfilled, leaving the sites in a state of ruin. This attempt at commodification, even when it does not materialize, can serve as a discursive framework that neutralizes deeper moral and historical issues related to property and destruction, thus supporting the broader regime of denial. The publication of Alice von Bieberstein’s book, “Temptations in Ruin: Sovereign Accumulation and the Making of Post-Genocide Turkey,” delves into these dynamics.

Parallel cancellation in Nagorno-Karabakh

The cultural erasure pattern observed in western Armenia is crucial to understanding recent events in Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh). Armenian genocide is understood by some as a “continuous process of cancellation” through forced displacement, destruction of cultural heritage and denial of return.

- Ongoing ethnic cleansing. The forced displacement of more than 120,000 Armenians from the Artsakh in 2023 is explicitly presented as the “most recent phase of a genocide that never really ended”. Azerbaijan, supported by Turkey and Russia, has undertaken what is described as a “second ethnic cleansing” to ensure that the Armenians cannot return to Artsakh. The article “In the Shadow of Sham Trials: Hostages of a Genocide”, published on May 12, 2025, highlights that this pattern of erasure, which began in the Ottoman Empire, continued in Artsakh.

- Systematic cultural destruction. This ongoing process includes the systematic destruction of Armenian churches and monuments, a reality that persists even today. In Nakhijevan, Azerbaijan, for example, an impressive 98% of Armenian cultural heritage sites, including medieval monasteries, churches and cemeteries, were completely destroyed between 1997 and 2011. Following the 2020 conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, about 1,456 Armenian cultural monuments have passed under Azerbaijani control, many of which have been deliberately damaged or destroyed. Azerbaijan is reported to systematically destroy and plunder Armenian houses, erasing the cultural heritage and repopulating the region with Azerbaijani settlers. The article “It is time to take Turkey to court”, published on May 27, 2025, reiterates that the Turkish government is still confronted with embarrassing memories of the crimes committed by its predecessor regime, stressing that the destruction of the Armenian cultural heritage is part of this.

- The intentionality of erasure. The indifference or international complicity in the face of these events, such as the signing of energy agreements with Azerbaijan during the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh, reflects a centuries-old deprioritization of Armenian existence. The debate on the demand for restitution and return of Western Armenia, raised in recent articles of 2025, underlines how Türkiye’s denial will not prevent Armenians from pursuing these crucial goals.

The consistent pattern of destruction, denial and commodification of the Armenian cultural heritage in both western Armenia and in Nagorno-Karabakh underlines a deliberate strategy to erase the history and presence of a people. For cultural heritage security experts, recognizing these interconnected processes is fundamental, as they highlight the vulnerability of heritage when it is linked to unresolved historical injustices and ongoing political agendas. The lack of international intervention and the “silence or complicity” surrounding these events allow a “cycle of cancellation to unfold without control”. This ongoing destruction represents an immense and irreplaceable loss for the world’s shared cultural heritage, calling for a more proactive and holistic approach to heritage protection in conflict and post-conflict areas.