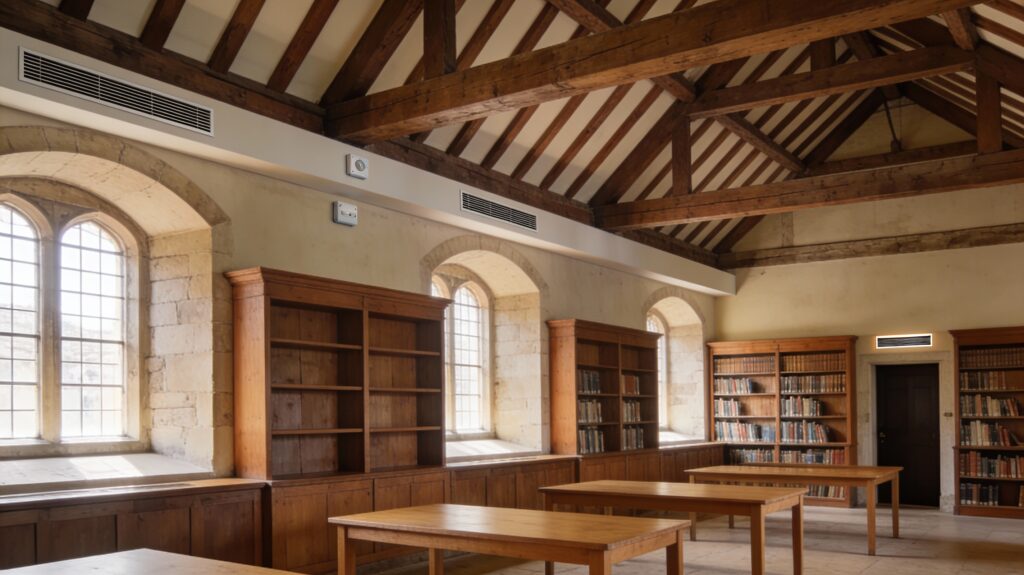

Why Cost–benefit Analysis matters for Historic Buildings

When deciding how to protect a historic building, it is not enough to ask “Is this measure technically effective?” The real question is whether the long‑term benefits of the measure justify its costs, including side effects on the building fabric.

A simple cost–benefit analysis (CBA) provides a structured way to compare different options and to decide how far to go with advanced systems such as HVAC upgrades or dedicated moisture control.

In the context of climate change, this type of CBA is especially useful because the main risks (overheating, damp, salt and moisture cycles, mould) are slow and cumulative, and the benefits of prevention are often visible only over decades. A good assessment therefore has to look far ahead, accept uncertainty, and give proper weight to the cultural value of the building, not just to repair bills.

How climate change threatens historic buildings

Climate change affects historic buildings through several pathways, and each one suggests different protection strategies:

- Rising temperatures and heatwaves

These can cause overheating, higher cooling demand, and physical stress on materials such as timber, adhesives and finishes. In this case, the focus is often on improved or more intelligent cooling systems (for example, advanced HVAC with smart controls) that limit temperature peaks inside the building. - More rain and higher humidity

Increased precipitation and humidity can lead to mould, mildew, insect and fungal attack, rising damp, water ingress and structural decay. Here, the logical response is better moisture management: dehumidification, adaptive ventilation, rainwater control and compatible repairs to keep water out while allowing the fabric to “breathe”. - Reduced heating needs

Warmer winters may reduce the need for heating, creating an apparent opportunity for energy savings. However, if heating is reduced too far or in the wrong way, the result can be colder, damper structures and more moisture problems. The emphasis then is on optimised HVAC and conservation heating, not simply on switching systems off.

A CBA helps to decide which of these systems is worth investing in for a particular building, under its specific climate and use conditions.

The main costs of advanced systems

Installing advanced HVAC or moisture‑control systems in a historic building is rarely straightforward. The main cost components to consider are:

- Initial capital costs

Non‑invasive installation techniques (for example, hiding ducts, avoiding damage to decorated surfaces) are more expensive than standard solutions. Specialised equipment such as high‑efficiency variable refrigerant systems or dedicated dehumidification units also increases the initial investment. - Operational and energy costs

New systems can be designed to be much more energy efficient than older plant, and in many cases they can reduce energy use significantly over time. At the same time, very precise humidity control usually consumes more energy than simple temperature control, so running costs must be carefully estimated and compared between options. - Maintenance and technical expertise

Advanced systems often need regular calibration, specialist servicing and monitoring. Over the lifetime of the system, these recurrent costs can be substantial and should be part of the CBA from the beginning. - Impact on space, appearance and fabric

Equipment needs plant rooms and duct routes. Poorly designed installations can disturb the historic character or, in the worst cases, change the moisture balance of the building in a way that creates new risks (for example, increased overheating or new condensation points behind internal insulation). These potential “side costs” must be considered alongside direct financial costs.

The benefits – more than just money

On the benefit side, the CBA needs to capture both direct, measurable savings and the less tangible, but crucial, heritage values that are being protected.

- Avoided damage and avoided interventions. Good climate‑control reduces cracking, surface loss, rot, corrosion and other forms of material degradation. This means fewer major repairs, fewer cycles of invasive restoration and lower conservation costs over the long term. Avoiding large‑scale mould or pest infestations can also prevent expensive emergency treatments.

- Energy savings and climate co‑benefits. Replacing outdated systems with efficient ones can cut energy use, reduce greenhouse‑gas emissions and lower energy bills. In a climate‑adaptation CBA, these “co‑benefits” increase the attractiveness of the investment.

- Lower risk of catastrophic loss. More stable indoor conditions reduce the chance of very costly failures (for example, sudden collapse of plaster ceilings or serious damage to collections). Insurers and funders may look favourably on well‑documented risk‑reduction measures, which can influence premiums and grant decisions.

- Preservation of authenticity and non‑use values. Perhaps the most important benefit is the one that is hardest to express in money: the preservation of authenticity, identity and continuity for future generations. A stable environment helps the original materials and finishes to survive, preserving the “truthfulness” of the building and its collections. Economists sometimes try to monetise these values using techniques that ask people how much they would be willing to pay to avoid losing a site, but for many heritage professionals it is enough to recognise that these are real, societal benefits that must be weighed in the analysis.

Making decisions under uncertainty

For climate‑adaptation measures, the analysis must accept that many parameters are uncertain: future climate trajectories, future use of the building, future energy prices and future conservation standards. A few practical points can help:

- Look at long time horizons (for example, 50–100 years), because both damage and benefits accumulate slowly.

- Use conservative assumptions: when in doubt, avoid over‑promising savings or under‑estimating risks, especially for very sensitive buildings.

- Compare several scenarios rather than seeking a single “correct” number. This highlights how sensitive the decision is to changes in the assumptions.

Some organisations choose to set a minimum benefit‑to‑cost ratio above 1 (for example, 1.5) for such investments, to reflect these uncertainties and to ensure that only clearly beneficial projects are approved. The exact threshold is a policy choice, but the principle is that the expected benefits should comfortably exceed the costs.

A simpler way to think about the fire‑protection example

The same logic applies when comparing, for example, a basic package of fire measures (extinguishers, staff training, simple improvements) with a more expensive automatic system such as water mist in a high‑risk, wooden or thatched historic structure.

- The basic package is cheaper, but leaves a relatively higher probability of a catastrophic fire.

- The advanced system costs more initially and each year, but greatly reduces that probability and improves safety margins for the collection and the building.

Rather than focusing on formulas, decision‑makers can ask:

- How much more do we spend over the life of the system for the advanced option?

- How much more fire risk does the basic option leave us with?

- Given the value and irreplaceability of the asset, is it acceptable to live with that higher risk?

If the realistic probability of a major loss is only slightly below the level at which the advanced system becomes economically justified, the decision is very sensitive to the risk estimate. In a fragile, high‑value heritage building, this often argues for choosing the safer option, because even a small underestimation of risk could lead to a devastating loss.

Key message for practitioners

A well‑designed cost–benefit analysis does not reduce heritage to a spreadsheet. Instead, it helps professionals to:

- Make transparent how much is being spent, on what timeframe, and for which types of benefit.

- Compare alternative solutions fairly, including their side effects on fabric and use.

- Explain to funders and owners why a certain level of protection is necessary, especially where the measures are costly or visually intrusive.

In the context of climate change and evolving hazards, adaptation measures are not a luxury. They are a structured, justified investment in the long‑term survival of irreplaceable cultural assets.