Backdraft at Historic Hotel Fire in Escanaba (USA)

A 161-year-old landmark hotel, a complex multi-occupancy historic structure, a ventilation-controlled fire in a concealed ceiling space, and a near‑fatal thermal event that fortunately injured no one: the House of Ludington fire in Escanaba is a interesting case study for historic-building fire safety professionals.

The building and its uses

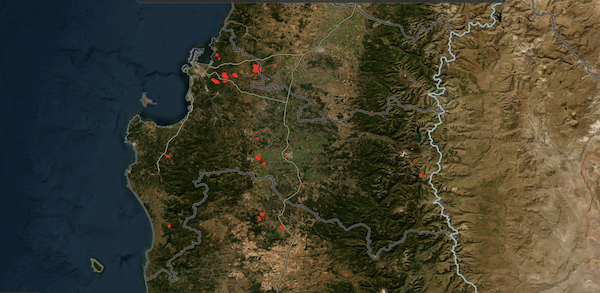

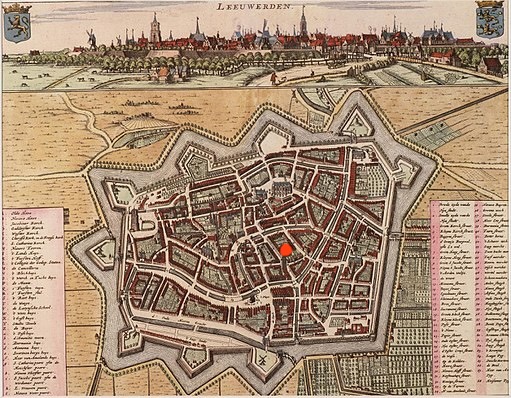

The House of Ludington is a multi-storey brick hotel at the eastern end of Ludington Street in downtown Escanaba, originally built in 1864 and progressively enlarged with wings and additions through the early 20th century to exceed 100 rooms. Over time it incorporated some of the earliest modern services in the region (electricity, steam heat, baths) and, more recently, bar and lounge areas, creating a highly stratified building with different construction ages, voids, and service runs.

Until 6th December, it functioned as a mixed-use historic property combining hotel rooms, long‑term tenants’ units, hospitality spaces and back‑of‑house service rooms, with a significant number of residents and employees depending on it for housing and income.

Sequence of events and fire development

On the morning of December 6, 2025, staff noticed a persistent smell of burning wood but were initially unable to locate the source, prompting a call to Escanaba Public Safety at about 10:33 a.m. Responders systematically searched the bar, main floor and basement with thermal imaging cameras, then moved to upper levels while other officers conducted an external walk‑around, illustrating good practice in structured investigation of an odor-of-smoke call in a large, compartmented historic structure.

Externally, white smoke was observed from a dormer above the main entrance, while internally a third‑floor storage room near an elevator was found filling with smoke. Residents and staff were evacuated.

Officers then opened the ceiling in the storage room, exposing flames in a concealed space, and almost immediately a violent thermal event occurred, described operationally as “flashover” that threw two public safety officers down a flight of stairs, who nevertheless escaped uninjured. The fire then spread rapidly toward the west side of the building and was fought for several hours, with crews and support agencies on scene until about 16:30 and the building ultimately considered a likely total loss due to collapse of ceilings, inaccessible stairways, flooding and major structural damage.

The causes of the fire at the moment this post is published remain unknown.

Backdraft, flashover, and concealed historic voids

From a fire dynamics perspective, the event in the storage room is highly suggestive of a backdraft or closely related ventilation-driven event occurring in a concealed ceiling space that had been burning in an under‑ventilated regime.

In a backdraft, a fire in a confined, poorly ventilated compartment consumes available oxygen while continuing to generate superheated, fuel-rich gases; visible flames may diminish, but temperature and gas concentration remain high. When an opening is created (for example, by pulling ceiling material) and fresh air suddenly enters and mixes with these gases, ignition can produce a violent deflagration and pressure wave that can throw firefighters or occupants and rapidly extend fire into adjacent spaces.

This differs from classic flashover, which is primarily driven by radiative feedback within a compartment that causes nearly simultaneous ignition of exposed combustibles once a critical temperature is reached; however, in practice, ventilation-controlled fires in concealed voids of historic buildings may present hybrid or ambiguous phenomena, and field descriptions often label any sudden transition as “flashover.”

Key contributing factors in heritage structures include: extensive concealed combustible construction above ceilings, multiple generations of service penetrations, and relatively tight external envelopes (e.g., modernized windows and doors) that favor oxygen depletion and accumulation of pyrolysis products before openings are made.

Human impact: tenants, employees and community

The House of Ludington fire did not result in casualties, which the general manager rightly emphasized as the day’s most important outcome: every life was saved despite a violent interior event and extensive structural involvement.

However, the social and economic losses are substantial: multiple long‑term residents have suddenly been rendered homeless, employees have lost their workplace and income stream, and an important node in Escanaba’s downtown hospitality and tourism economy is offline, with ripple effects on surrounding businesses.

Local institutions responded by rapidly organizing support mechanisms, including a dedicated relief fund through a local bank and digital donation channels to assist employees and residents, demonstrating a strong community resilience culture around a heritage asset that has long served as a symbol and economic anchor for the waterfront area.

For professionals, these responses underscore that fire risk management in historic buildings must explicitly consider not just cultural value but also the building’s role in local housing, employment and social infrastructure.

Lessons for historic-building fire safety practice

Several technical and organizational lessons emerge for practitioners:

- Odor-of-smoke calls in historic buildings must be treated as high‑priority events, with structured search plans, use of multiple thermal imagers, and early involvement of command support, given the propensity for fires to develop unseen in concealed voids.

- Pre‑incident planning should map concealed spaces, vertical shafts and service chases (especially near elevators and storage rooms), and consider their potential to support ventilation‑limited fires and backdraft‑type events when openings are created.

- Tactics should integrate backdraft indicators and gas-cooling/ventilation strategies: signs such as smoke‑filled but flame‑poor compartments, pulsating smoke at small openings, or white/grey smoke from roof voids should trigger cautious, controlled opening of ceilings and, where possible, coordinated ventilation rather than aggressive blind overhaul.

Equally crucial is the role of evacuation planning in heritage hotels and multi‑occupancy historic buildings. A clear, practiced plan allowed staff and residents to be evacuated rapidly once conditions were recognized as hazardous, avoiding injuries even when the interior situation escalated suddenly.

For similar properties, this means: tailored procedures for staged or full evacuation; regular training for staff on alarm recognition, route management and assisting vulnerable occupants; and coordination protocols with public safety so that evacuation, search, and fire investigation actions are synchronized, particularly when dealing with subtle early signs like burning odors rather than obvious flames.