Niscemi (Italy), when the Earth takes back Memory

Preserving what remains — even digitally — will depend on urgent coordination between geological experts, heritage conservators, and institutions capable of offering shelter to a displaced archive

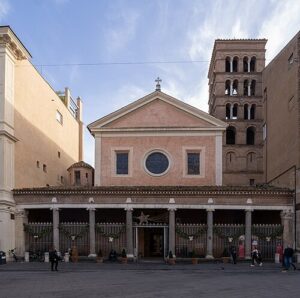

House on the edge of the landslide near the Angelo Marsiano Library, Niscemi (Sicily). Image from open sources / CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/). Non-commercial use with attribution as required by the license.

In the town of Niscemi, in southern Sicily, a slow-moving landslide has been advancing for months, carving cracks through streets and threatening dozens of homes.

The movement, triggered by prolonged seasonal rains and the inherent instability of clay soils, has reached the heart of the historic center. Among the buildings now at risk is the Angelo Marsiano Library, a private collection that has become one of the main custodians of Niscemi’s documentary heritage.

The library houses more than four thousand volumes: nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century publications on the town’s origins, monographs on the nearby Sughereta di Niscemi nature reserve, family archives, parish registers, and thousands of pages recording oral traditions and the evolution of the local dialect.

For decades, civic volunteers, local scholars, and the Marsiano family have contributed to building this collection — a rare example of a library that truly mirrors the social and environmental history of its territory.

Now, the structure itself stands on ground that is visibly shifting. Deep fissures run through its walls, and the surrounding terrain has lowered in places, leaving parts of the building suspended over the void. Technical assessments suggest that stabilization or recovery would require massive earthworks and years of consolidation, far beyond the town’s current capacity.

Even the relocation of the books poses a serious challenge: the materials are delicate, the humidity uncontrolled, and no available storage site fully meets minimal conservation standards. In effect, the entire library is trapped within the risk zone.

Local authorities, cultural associations, and volunteers are documenting the collection as long as conditions allow, photographing catalogs and creating digital copies where possible. Yet time is closing in.

Each new rainfall accelerates the slope’s movement, and with every passing day the probability increases that physical access will no longer be possible.

The story unfolding in Niscemi is more than a local emergency. It is a reminder that cultural heritage can vanish not only through fire or neglect, but also through the slow, invisible processes of a changing landscape.

When the ground itself begins to erase memory, communities are forced to confront how fragile and intertwined their natural and cultural environments truly are.

Preserving what remains — even digitally — will depend on urgent coordination between geological experts, heritage conservators, and institutions capable of offering shelter to a displaced archive. The lessons from Niscemi will resonate wherever human history depends on the stability of the earth beneath it.