Protecting Monuments: ICOMOS Charter and Fire Safety Principles

As far as we know, education or training of professionals involved in safety assessment of historic buildings is an area that could be strongly improved.

The Shuri Castle in a 2025 picture (Image: Jun, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shuri_Castle_under_reconstruction_on_23_December_2025.jpg)

Updated February 2026

The training and education of professionals involved in safety assessment of historic buildings remains an area requiring significant improvement. The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), a global non-governmental organization associated with UNESCO dedicated to conservation of the world’s monuments and sites, has produced foundational documents that should inform every fire safety intervention at cultural heritage sites.

Since its establishment, ICOMOS has developed an extensive framework of international charters, principles and guidelines addressing conservation and restoration. Among these, the 2003 Charter — “Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage” — ratified by the ICOMOS 14th General Assembly in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, presents crucial principles for safety professionals working with cultural heritage buildings.

The ICOMOS Charter Framework

The ICOMOS charter system comprises multiple specialized documents addressing different aspects of heritage conservation:

- International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (Venice Charter 1964) — the foundational document establishing conservation philosophy

- Historic Gardens (Florence Charter 1981)

- Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas (Washington Charter 1987)

- Charter for the Protection and Management of the Archaeological Heritage (1990)

- Charter on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (1996)

- International Cultural Tourism Charter (1999)

- Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage (1999)

- Principles for the Preservation of Historic Timber Structures (1999)

- ICOMOS Charter – Principles for the analysis, conservation and structural restoration of architectural heritage (2003)

- ICOMOS Principles for the preservation and conservation/restoration of wall paintings (2003)

Each charter addresses specific heritage types and conservation challenges, but the 2003 structural restoration charter holds particular relevance for fire safety professionals because it explicitly addresses safety requirements alongside conservation principles.

Fire Safety in ICOMOS Principles

Multi-disciplinary Approach and Consensus Building

The 2003 Charter’s first principle states that “conservation, reinforcement and restoration of architectural heritage requires a multi-disciplinary approach”. This synthesis captures the inherent difficulties of any intervention on heritage buildings: they require interaction among users, conservators and safety professionals.

For fire safety practitioners, this principle mandates that:

- Fire protection measures cannot be designed in isolation from conservation objectives

- Structural engineers, conservators, architects, fire safety engineers and building managers must collaborate from the earliest planning stages

- User needs and operational requirements must be balanced against protection objectives

- Traditional building techniques and historical construction methods must be understood before proposing modern interventions

The Charter warns that “the value of architectural heritage is not only in its appearance, but also in the integrity of all its components as a unique product of the specific building technology of its time”. This principle directly impacts fire safety interventions: the removal of inner structures while maintaining only façades does not fit conservation criteria, yet fire safety improvements—such as creating wider egress routes or installing compartmentation—may propose exactly such alterations.

Principle 1.5 reinforces this requirement: “when any change of use or function is proposed, all the conservation requirements and safety conditions have to be carefully taken into account”. This is not always understood in the conservation community, where functional adaptation may be prioritized over life safety, or vice versa. The Charter demands consensus among all three main actors: users/owners, conservationists and safety professionals.

The Medical Analogy: Diagnosis Before Treatment

Paragraph 1.6 of the Charter describes a process for defining causes and responses to safety issues that mirrors medical practice:

“The peculiarity of heritage structures, with their complex history, requires the organisation of studies and proposals in precise steps that are similar to those used in medicine: anamnesis, diagnosis, therapy and controls, corresponding respectively to the searches for significant data and information, individuation of the causes of damage and decay, choice of the remedial measures and control of the efficiency of the interventions.”

This iterative, evidence-based methodology contrasts with prescriptive fire code compliance approaches. International and national fire safety standards typically follow a different process focused on code compliance, hazard identification and risk-based design. A specific training program bridging both methodologies—the heritage “medical” model and the fire engineering risk assessment model—would benefit safety professionals working in this specialized field.

Emergency Operations and Reversibility

Principle 1.7 holds particular importance for post-fire and post-disaster response:

“No action should be undertaken without having ascertained the achievable benefit and harm to the architectural heritage, except in cases where urgent safeguard measures are necessary to avoid the imminent collapse of the structures (e.g. after seismic damages); those urgent measures, however, should when possible avoid modifying the fabric in an irreversible way.”

This provision acknowledges that emergency operations—such as those following earthquakes or fires—require rapid structural stabilization, but even urgent interventions should minimize irreversible alterations. Post-earthquake shoring operations, emergency fire debris removal and temporary weather protection must all keep this principle in mind.

Performance-Based Approach to Safety

Proposition 2.8 of the Charter explicitly recognizes the limitation of prescriptive codes when applied to historic buildings:

“Often the application of the same safety levels as in the design of new buildings requires excessive, if not impossible, measures. In these cases specific analyses and appropriate considerations may justify different approaches to safety.”

This principle directly endorses the performance-based approach commonly applied in building fire safety engineering. Performance-based design identifies the best solution from multiple possible safety measures and is often the only viable path to improve safety in historic buildings without unacceptable heritage impact.

Related propositions reinforce this approach:

- Proposition 3.5: “Each intervention should be in proportion to the safety objectives set, thus keeping intervention to the minimum to guarantee safety and durability with the least harm to heritage values”.

- Proposition 3.8: “At times the difficulty of evaluating the real safety levels and the possible benefits of interventions may suggest ‘an observational method’, i.e. an incremental approach, starting from a minimum level of intervention, with the possible subsequent adoption of a series of supplementary or corrective measures”.

These propositions align closely with modern fire risk management methodologies that prioritize tailored, risk-informed interventions over blanket code compliance.

Material Authenticity and Fire Protection Conflicts

Several Charter propositions create direct tension with conventional fire protection measures:

- Proposition 3.12: “Each intervention should, as far as possible, respect the concept, techniques and historical value of the original or earlier states of the structure and leaves evidence that can be recognised in the future”.

This principle can create fire safety challenges due to the difficulty of integrating fire-rated materials with the need to preserve historical techniques. Modern fire-resistant boards, intumescent coatings and suppression system piping may conflict with authentic finishes, construction methods and aesthetic integrity.

- Proposition 3.14: “The removal or alteration of any historic material or distinctive architectural features should be avoided whenever possible”.

- Proposition 3.15: “Deteriorated structures whenever possible should be repaired rather than replaced”.

Both propositions limit the fire safety engineer’s toolkit. Replacing combustible historic roof structures with fire-resistant modern materials, or removing ornate but flammable wall hangings, would violate these principles.

However, Proposition 3.16 shows greater awareness of the fire safety dilemma: “Imperfections and alterations, when they have become part of the history of the structure, should be maintained so far as they do not compromise the safety requirements“. This clause acknowledges that safety requirements may override pure conservation orthodoxy when life safety is at stake.

Critique of the Charter’s Practical Applicability to Fire Safety

Strengths

The 2003 ICOMOS Charter provides an essential philosophical and procedural framework that fire safety professionals must respect when working with heritage buildings. Its strengths include:

- Explicit recognition of safety as a legitimate conservation concern — Unlike earlier conservation documents that treated safety as secondary to authenticity, the 2003 Charter integrates safety requirements into the core conservation process.

- Endorsement of performance-based and risk-informed approaches — By acknowledging that “the same safety levels as in new buildings” may require “excessive, if not impossible measures,” the Charter opens the door to tailored fire engineering solutions rather than rigid code compliance.

- Requirement for multi-disciplinary collaboration — The Charter’s insistence on involving conservators, engineers and users from the start helps prevent late-stage conflicts between fire safety retrofits and heritage values.

- Iterative, evidence-based methodology — The “medical analogy” process promotes thorough investigation before intervention, reducing the risk of inappropriate or excessive fire protection measures.

Limitations and Gaps

Despite its strengths, the Charter has significant limitations when applied to fire risk management:

- Fire is addressed only implicitly, not explicitly — The Charter discusses “safety” in general terms, primarily focusing on structural and seismic safety. Fire risk—historically the leading cause of catastrophic heritage loss—receives no dedicated section or specific guidance.

- No guidance on balancing life safety against heritage values — While Proposition 3.16 acknowledges that safety requirements may override conservation, the Charter provides no framework for deciding when this threshold is reached. Should a sprinkler system be installed if it means drilling through historic frescoed ceilings? The Charter offers no decision-making hierarchy.

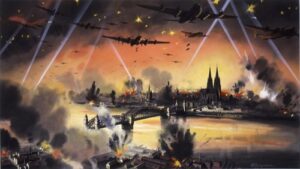

- Limited recognition of fire as a “total loss” hazard — Seismic damage and structural decay are incremental and often repairable. Fire, by contrast, can result in complete and irreversible loss within hours (e.g., National Museum of Brazil 2018, Shuri Castle 2019, Glasgow School of Art 2018). The Charter’s emphasis on minimal intervention may inadvertently discourage robust fire protection that could prevent total loss.

- Insufficient guidance on active versus passive fire protection — The Charter does not differentiate between passive measures (compartmentation, fire-resistant materials) that may be more compatible with historic fabric, and active systems (sprinklers, detection) that offer superior protection but require visible retrofits.

- No mention of emergency preparedness, detection or suppression systems — Modern fire risk management emphasizes early detection, automatic suppression, emergency planning and community engagement. The Charter’s focus on structural interventions overlooks these non-invasive, highly effective fire risk reduction measures.

- Ambiguity regarding “acceptable risk” — The Charter does not define what constitutes adequate safety for heritage buildings, leaving fire engineers without clear performance targets.

Case Studies of Charter Implementation in Fire Safety Context

Case Study 1: Notre-Dame de Paris Fire Protection (Pre-2019 Fire)

Before the catastrophic April 2019 fire, Notre-Dame Cathedral had limited fire protection measures despite its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The decision not to install automatic sprinklers in the roof void and attic spaces reflected interpretation of ICOMOS principles prioritizing minimal intervention and aesthetic preservation.

Charter Principles Applied:

- Proposition 3.12 (respect original techniques) and 3.14 (avoid alteration of historic material) were interpreted to exclude modern suppression systems from the 13th-century oak roof structure (“the forest”).

- The multi-disciplinary approach (Principle 1.1) was followed: architects, conservators and fire officials collaborated, but conservation concerns dominated.

Outcome:

The 2019 fire during renovation work destroyed the entire roof structure, the spire and significant portions of the interior vaulting. Firefighters discharged massive quantities of water causing additional damage. The lack of automatic suppression—justified by heritage preservation—resulted in far greater heritage loss than sprinkler piping ever would have caused.

Lesson:

Strict adherence to minimal intervention principles (3.12, 3.14) without adequate weight given to Proposition 3.16 (“safety requirements”) can lead to catastrophic total loss. The Charter’s failure to explicitly address fire as a “total loss” scenario contributed to this imbalance.

Case Study 2: Shuri Castle, Okinawa, Japan (2019 Fire)

Shuri Castle, a reconstructed UNESCO World Heritage Site and symbol of Okinawan identity, burned completely in October 2019 due to an electrical fire during preparations for a cultural event. The wooden structure had minimal fire detection and no automatic suppression.

Charter Principles Applied:

- The reconstruction after World War II destruction followed ICOMOS principles by using traditional Ryukyuan construction methods, including extensive combustible timber framework.

- Proposition 3.7 (choice between traditional and innovative techniques) led to preference for authentic materials over fire-resistant alternatives.

Outcome:

The main hall and multiple structures burned to the ground in hours. The absence of sprinklers—consistent with traditional construction authenticity—meant total loss.

Lesson:

When applying Charter Proposition 3.7 (traditional versus innovative techniques), fire risk must be explicitly evaluated. The Charter’s language “bearing in mind safety and durability requirements” was insufficiently weighted against authenticity concerns.

Case Study 3: Windsor Castle Fire Response (1992)

The 1992 Windsor Castle fire offers a more positive case study where ICOMOS principles informed both emergency response and reconstruction.

Charter Principles Applied:

- Principle 1.7 (urgent safeguard measures should avoid irreversible modification) guided post-fire emergency stabilization: firefighters and engineers minimized demolition and preserved as much fire-damaged fabric as possible for assessment.

- The “medical analogy” process (Principle 1.6) structured the recovery: detailed anamnesis (documentation of pre-fire state), diagnosis (structural assessment), therapy (selective repair/reconstruction) and controls (monitoring).

- Proposition 2.8 (different approaches to safety may be justified) supported a performance-based fire engineering solution for the rebuilt St. George’s Hall, incorporating modern fire protection while maintaining historic character.

Outcome:

Windsor Castle reopened after five years with improved fire safety (compartmentation, sprinklers, detection) integrated sensitively into restored and reconstructed spaces. The project is widely regarded as exemplary application of conservation principles alongside modern fire protection.

Lesson:

Successful integration of fire safety and ICOMOS Charter principles is achievable when all parties collaborate early, use performance-based design methods and apply the iterative “medical analogy” process.

Cross-Reference to Other International Charters and Guidance

The ICOMOS 2003 Charter should be read alongside other international heritage and fire safety documents:

UNESCO Fire Risk Management Guide (2024)

UNESCO’s recently published Fire Risk Management Guide: Protecting Cultural and Natural Heritage from Fire provides the operational framework that the ICOMOS Charter lacks. The Guide explicitly addresses.

- Fire Risk Management Plan (FRMP) development methodology

- Ignition source control and combustible material management

- Detection, suppression and compartmentation strategies

- Emergency preparedness, response and recovery

- Wildfire protection for heritage landscapes

- Community engagement and traditional ecological knowledge

Relationship to ICOMOS Charter:

The UNESCO Guide operationalizes ICOMOS principles within fire-specific contexts. For example:

- The Guide’s FRMP methodology (6-step process) mirrors the Charter’s “medical analogy” (anamnesis-diagnosis-therapy-control).

- The Guide’s emphasis on “proportionate measures” and “tailored solutions” reflects Charter Propositions 3.5 and 2.8.

- The Guide fills the Charter’s gap by providing specific fire protection options (sprinklers, water mist, detection types) that can be evaluated for heritage compatibility.

Practical Application:

Fire safety engineers should use the UNESCO Guide as the technical implementation tool for applying ICOMOS Charter philosophical principles to fire risk scenarios.

NFPA 914: Code for Fire Protection of Historic Structures (2019)

NFPA 914, developed by the U.S. National Fire Protection Association, offers a performance-based code specifically for historic buildings.

Relationship to ICOMOS Charter:

- NFPA 914 explicitly references the Venice Charter and ICOMOS conservation philosophy in its scope and purpose.

- The code’s performance-based approach aligns with Charter Proposition 2.8 (different safety approaches may be justified).

- NFPA 914 Chapter 4 requires a “statement of significance” documenting heritage values—operationalizing the Charter’s requirement to understand “the integrity of all its components”.

Divergence from Charter:

Unlike the Charter’s emphasis on minimal intervention, NFPA 914 prioritizes life safety and may require substantial fire protection systems if risk assessment warrants. The code provides a clearer decision hierarchy: life safety first, heritage preservation second.

Historic England Guidance: Fire Safety Management in Traditional Buildings (2017)

Historic England’s practical guidance applies ICOMOS principles to the UK regulatory context.

Key Contributions:

- Detailed case studies showing compatible integration of detection and suppression systems in listed buildings

- Risk assessment templates tailored to heritage buildings

- Guidance on negotiating with fire authorities and building control officials

- Options analysis comparing heritage impact versus fire protection effectiveness for different system types

ICOMOS-ICORP Principles (Risk Preparedness)

The ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Risk Preparedness (ICORP) has developed supplementary guidance addressing disaster risk reduction for heritage, including fire.

Relationship to 2003 Charter:

ICORP principles expand the Charter’s brief mention of emergency measures (Proposition 1.7) into comprehensive risk preparedness frameworks covering:

- Hazard identification and vulnerability assessment

- Emergency response planning and drills

- Community engagement and capacity building

- Post-disaster recovery and “building back better”

Recommendations: Bridging the Charter and Fire Safety Practice

To improve practical application of ICOMOS Charter principles in fire safety contexts, the following measures are recommended:

For ICOMOS and the Heritage Conservation Community

- Develop fire-specific supplementary guidance to the 2003 Charter that explicitly addresses fire risk management, automatic suppression systems, detection strategies and emergency preparedness.

- Clarify the decision hierarchy when life safety and heritage values conflict, providing clearer thresholds for when Proposition 3.16 (“safety requirements”) overrides minimal intervention principles.

- Integrate the UNESCO Fire Risk Management Guide into ICOMOS training programs and encourage National Committees to adopt it alongside the 2003 Charter.

- Promote case study documentation of successful fire safety/heritage integration projects (e.g., Windsor Castle, PREVENT sites) to demonstrate Charter-compliant fire protection.

For Fire Safety Professionals

- Mandatory training in ICOMOS Charter principles for fire engineers, code officials and consultants working with heritage buildings. This should include the “medical analogy” methodology and understanding heritage significance assessment.

- Adopt multi-disciplinary team approaches from project inception, involving conservators, archaeologists, historians and heritage architects alongside fire engineers.

- Use performance-based design as standard practice for heritage buildings, citing Charter Proposition 2.8 to justify alternatives to prescriptive code compliance.

- Document heritage impact assessments for all proposed fire protection measures, evaluating both “action” (installing systems) and “inaction” (not installing systems) scenarios.

For Regulatory Authorities

- Recognize ICOMOS Charter in building codes and fire safety regulations as legitimate basis for alternative compliance methods for heritage buildings.

- Establish heritage fire safety specialist roles within fire departments and building control agencies to facilitate Charter-compliant approvals.

- Require Fire Risk Management Plans (per UNESCO Guide methodology) for all heritage buildings as condition of occupancy permits.

Conclusion

The ICOMOS 2003 Charter — Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage — provides an essential foundation for integrating fire safety into heritage conservation practice. Its endorsement of multi-disciplinary collaboration, performance-based approaches and proportionate intervention offers a philosophical framework compatible with modern fire risk management.

However, the Charter’s limitations—particularly its implicit rather than explicit treatment of fire, lack of guidance on life safety trade-offs and absence of operational detail—create gaps that the UNESCO 2024 Fire Risk Management Guide and other specialized documents must fill.

Fire safety professionals working with heritage buildings should view the ICOMOS Charter not as an obstacle but as a collaborative framework requiring them to think beyond prescriptive codes and engage deeply with heritage values, traditional construction methods and conservation objectives. Conversely, conservation professionals must recognize that the Charter’s own Proposition 3.16 prioritizes safety requirements and that preventing total loss through fire demands robust, sometimes visible, fire protection interventions.

Education and training bridging both communities—teaching conservators fire behavior science and teaching fire engineers heritage significance assessment—remains the most critical need. The ICOMOS Charter should be considered a foundational pillar in any fire safety professional’s education when assessing safety and designing measures for historic buildings and monuments