The Growing Threat of Arson Against Historic Places of Worship

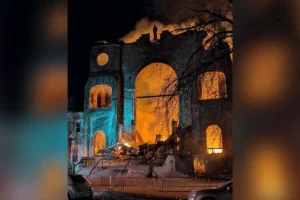

Across continents and denominations, houses of worship (many of which are listed or historic buildings) are increasingly being targeted by deliberate acts of arson—not by accident or natural disasters, but by intent.

In recent months, churches, mosques, and temples with significant historic or cultural value have become increasingly common targets in a troubling global pattern. For fire safety professionals, this trend is not only a call to action but also a growing crisis that demands greater awareness, collaboration, and preventative strategies.

From remote towns in South Africa to cities across North America and Europe, these fires are far from isolated incidents. They reflect a dangerous intersection of ideology, neglect, and opportunity—often exploiting the openness that places of worship are founded on.

In Alberta, Canada, three individuals were recently charged in connection with the arson of a nearly century-old church, but investigators believe that others may still be involved, and the case is still unfolding. Hundreds of churches across Canada have been targeted in what officials describe as a wave of hate-motivated arsons.

In Arizona, a Catholic church in Casa Grande has begun planning to rebuild after a fire that authorities allege was intentionally set. Just days earlier, a fire swept through Beth El Bible Church in El Paso, Texas, resulting in an arson arrest following a political vigil on the premises.

South Africa has witnessed a disturbing cluster of attacks in recent weeks. In the Vhembe District, police have observed a surge in both arson and burglaries targeting churches. Simultaneously, in Thohoyandou and Limpopo, multiple church buildings have been destroyed in suspicious blazes, leaving faith communities devastated and fearful.

In Sweden, a mosque was reduced to rubble in what authorities suspect was a hate-motivated arson attack. Similar incidents have occurred in Spain, Ireland, and the United States, including Mississippi, Pennsylvania, and New York. In Brooklyn, a man was charged with setting fire to a church as part of an arson spree that also targeted residential buildings. These attacks vary in motive—some ideological, some opportunistic—but the outcome is consistent: sacred spaces were destroyed.

Beyond North America and Europe, West Africa has also seen a troubling escalation of religiously motivated arson. In Nigeria, a growing number of attacks on churches and Christian communities demonstrate how arson and related violence are being employed as instruments of terror. Earlier in 2025, Boko Haram raided several Christian villages in Borno State—among them Shikarkir, Yirmirmug, Njila, and Banziir—burning homes and churches, displacing thousands.

On January 1 in Kaduna State, a Fulani herdsmen attack destroyed the Evangelical Church Winning All building in Unguwar Rogo village. The International Criminal Court has been monitoring such incidents amid broader concerns about religious persecution and mass violence.

In Benue State, Catholic priests publicly condemned the burning of St. Paul’s Parish in Aye-Twar (Agu Centre), as well as the occupation of 26 outstations by armed herdsmen who had destroyed church facilities, pastoral residences, secretariats, and other properties.

These incidents underscore the significant challenges faced by faith communities in securing protection, particularly in rural or under-resourced areas where state presence is either weak or inconsistent.

Why places of worship are vulnerable

Religious buildings, by their nature, often prioritise openness and accessibility. Many remain unlocked for prayer, counselling, or community service, making them easy targets for those seeking to cause harm. Some are located in rural or underserved areas with limited fire detection and surveillance infrastructure. Others are historic buildings that lack modern fire-resistant materials or suppression systems.

Crucially, these sites often operate on tight budgets, prioritising spiritual and social services over physical security upgrades. This makes even basic deterrents—such as exterior lighting, fire alarms, and video surveillance—difficult to implement. Furthermore, since worship typically occurs only once or twice a week, many of these buildings remain empty for extended periods, further increasing the window for undetected arson.

The 2020 “Protection of Places of Worship” analysis of the European Commission

In 2020, the European Union news page provided an analysis of the threats and the assessment criteria recommended for places of worship. Such a page addresses the ongoing occurrence of attacks on individuals exercising their fundamental right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion in churches, mosques, synagogues, and other places of worship, with alarming consistency across Europe.

Anticipating, preventing, protecting, and responding to malicious acts of religious intolerance and violent radicalization necessitates multi-disciplinary and multi-stakeholder efforts that impact and are affected by the entire society. The term “place of worship” encompasses any temple, shrine, site, faith community centre, or religious school where worship to any religion is practised (the 2025 attack in the United States is one of the most evident cases of such an incident).

When designing tailored protection solutions, the fundamental principles to adhere to include threat identification and assessment, vulnerability assessment, likelihood evaluation, the selection of counter/mitigation measures, and the rehearsal and review of security plans.

A relevant fire safety standard

Places of worship may fall under the scope of NFPA 909 – Code for the Protection of Cultural Resource Properties – Museums, Libraries, and Places of Worship, which includes provisions for fire risk assessment, detection, suppression, and emergency planning in buildings with cultural, historical, or religious significance.

While not specific to religious facilities, the standard is often applied to churches, mosques, synagogues, and similar structures due to their frequent designation as cultural heritage sites. NFPA 909 outlines a risk-based approach that can support the development of comprehensive fire protection strategies, particularly in older buildings or those with high occupant loads and limited modern infrastructure.

How fire safety professionals can respond

For those working in fire prevention, response, and investigation, the rise in worship-site arson presents a unique and complex challenge. These are not merely structural fires—they are cultural crimes, often emotionally charged and politically sensitive. Our role extends beyond containment and cause analysis. It demands proactive engagement with religious institutions and law enforcement.

In high-risk areas, outreach and education can be powerful tools. Fire departments and safety consultants can collaborate directly with faith leaders to conduct risk assessments, identify vulnerabilities, and develop tailored emergency response plans. In some cases, offering free or subsidised safety audits may be a vital initial step—particularly for small congregations with limited resources.

Equally important is the need for fire professionals to assist in identifying patterns and collaborating across jurisdictions. When religious arson is treated solely as a local issue, we overlook its broader societal implications. Sharing data, investigative techniques, and community safety models can significantly contribute to breaking the cycle of repeat attacks.

One encouraging aspect of the recent surge in arson cases is the rapid apprehension of some suspects. In Mississippi, a man was recently convicted for vandalising and setting fire to a Latter-Day Saints church. In Ireland, a young man will soon face trial for a series of church fires in Donegal. However, in many other cases, investigations remain ongoing and unsolved.

Law enforcement and fire investigators cannot shoulder this burden alone. Religious institutions must be equipped—not only spiritually but structurally—to respond to threats. This includes investing in fire detection systems, implementing secure access policies, and cultivating relationships with local first responders.

Ultimately, safeguarding sacred spaces extends beyond preserving buildings; it encompasses safeguarding community trust. When a mosque or church is burned, the emotional and symbolic damage often far surpasses the monetary value of the property lost. Rebuilding is difficult; restoring a sense of safety is even harder.