Wildfires in Chile Damage Historic Heritage

Large-scale wildfires and other widespread emergencies are usually narrated in terms of hectares burned, people evacuated, houses destroyed and victims. The loss of historic buildings, cultural landscapes and community heritage remains a secondary line in most reports – if it is mentioned at all. Yet, for many communities, what burns in a few hours is not only square metres of timber and masonry, but fragments of identity: churches, neighbourhoods, landmarks, archives, places of everyday memory.

Heritage losses that disappear in the numbers

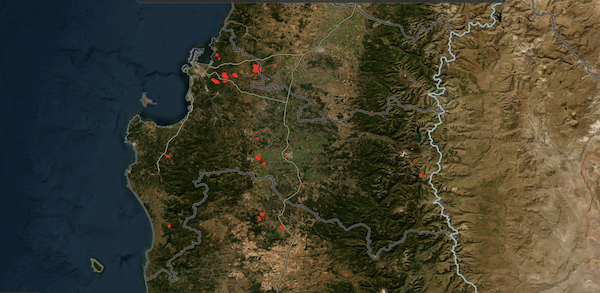

The 2026 wildfires in Chile’s Biobío region are a recent example. International media rightly focus on fatalities, thousands of displaced residents and entire towns like Lirquén and Penco partially wiped out between 18 and 20 January 2026. Only a few local reports mention that among the ruins lies a historic church in Lirquén built in 1913, explicitly described as part of the area’s religious heritage and as a social centre for vulnerable neighbourhoods. For national statistics, it is “one building” in the count of several hundred destroyed; for the community, it is a piece of collective memory that cannot be rebuilt on a like‑for‑like basis.

This pattern is not new. UNESCO’s recent Fire riskhttps://www.fireriskheritage.net/publicationsand-research-documents-of-risk-to-cultural-heritage/unesco-document-on-fire-protection/ management guide: protecting cultural and natural heritage from fire (2024) stresses that fires are now one of the most serious and destructive threats to both cultural and natural heritage, citing iconic cases like Notre‑Dame in Paris and the Brazilian National Museum, but also wildfires in heritage landscapes such as Rapa Nui. At the same time, UNESCO observes that many World Heritage properties still lack dedicated disaster risk plans, and that national and local emergency mechanisms rarely integrate heritage expertise in their operations.

Why heritage is structurally under‑protected

From a risk engineering perspective, the vulnerability of heritage in large‑scale events is structurally underestimated for at least three reasons:

- Planning scales and categories. Emergency planning tools – evacuation maps, hazard models, impact statistics – work with categories like “residential”, “industrial”, “critical infrastructure”. Historic buildings and cultural assets are either invisible in these layers or diluted in generic classes, unless they belong to a short list of formally protected monuments.

- Metrics focused on life safety and direct damage. Traditional performance criteria focus (correctly) on life safety and, to a lesser extent, on direct economic loss. The specific value of heritage – symbolic, historical, social – is rarely translated into risk metrics, and thus hardly enters cost–benefit analyses or prioritisation of mitigation measures. Gaps between heritage management and emergency management

As UNESCO notes, heritage institutions and emergency services often operate on parallel tracks, with limited exchange of data, scenarios and planning assumptions. This means that when a major wildfire or multi‑hazard event occurs, the protection of heritage assets is left to ad‑hoc decisions in the heat of the moment, rather than being embedded in pre‑agreed strategies.

Wildfires, climate change and new interfaces

Climate change amplifies this problem by expanding the wildland–urban interface (WUI) around historic towns, rural churches, archaeological sites, traditional landscapes. Fires that once remained confined to forests now reach the edges of historic centres, touch pilgrimage routes, threaten open‑air sites and museums, and attack fragile structures never designed for flame, ember and smoke exposure.

Recent work on fire vulnerability assessment of historic buildings shows how many layers of risk converge on heritage assets: combustible finishes, outdated electrical systems, limited compartmentation, lack of detection and suppression, difficulties in evacuating both people and movable artefacts. In a wildfire context, these intrinsic vulnerabilities are combined with long response times, simultaneous demands on firefighting resources, and complex evacuation patterns in surrounding communities.

What a heritage‑sensitive approach should look like

From the perspective of Fire Risk Heritage, integrating heritage into large‑scale fire and emergency planning means:

- Making heritage visible in risk layers. Cultural and historic assets – not only monumental sites, but also historic churches, archives, traditional districts – should appear as explicit layers in hazard and exposure maps used for wildfire and multi‑hazard planning.

- Including heritage in emergency objectives and scenarios. Objectives for emergency plans should not stop at “no casualties and minimum disruption”, but incorporate explicit heritage‑related goals: protection of key assets, prioritised defence lines, fallback strategies for artefacts and records, criteria for “acceptable loss” that reflect cultural value.

- Bridging the gap between sectors. Heritage professionals, fire engineers and emergency planners need shared tools: vulnerability indices tailored to historic buildings, performance‑based criteria that include heritage significance, pre‑incident plans where asset protection is integrated with evacuation and response logistics.

- Learning from events and documenting losses. After each major wildfire or crisis, the documentation of heritage damage – including “everyday heritage” not in official lists – should become part of the post‑event analysis, on the same level as infrastructure and housing losses. Without this, the systematic under‑representation of heritage in statistics will continue.

A call for explicit heritage metrics in fire risk

The Biobío fires, like many before them, remind us that what is not measured is not protected. If historic buildings and cultural landscapes remain invisible in the way risk is quantified and communicated, they will continue to be collateral victims of decisions optimized for other metrics. The emerging international guidance – from UNESCO’s fire risk management guide to new vulnerability indices tailored to historic churches and sites – offers a framework to correct this bias, but its principles need to be adopted concretely in wildfire and large‑scale emergency planning.

Fire Risk Heritage will continue to document these “hidden” losses and to promote tools and methods that bring heritage explicitly into the equations of fire risk, evacuation and resilience – before the next season’s fires redraw, once again, the map of what a community can afford to lose.